How to Infuse Landscapes with Mood and Translucence

Eric Angeloch has taken the proverbial “road less traveled” to create stunning landscapes imbued with mood, atmosphere, and light. Here’s how.

By Robert K. Carsten

To grow up in an enclave nestled in the Catskills — one that has long been a haven for other creatives — seems idyllic. Couple this with having been reared in a family where making and teaching art was an integral part of daily life and you have the creative childhood of Eric Angeloch. Learn about his background and his intuitive painting process, followed by his demonstration “9 Steps Toward Translucence,” below.

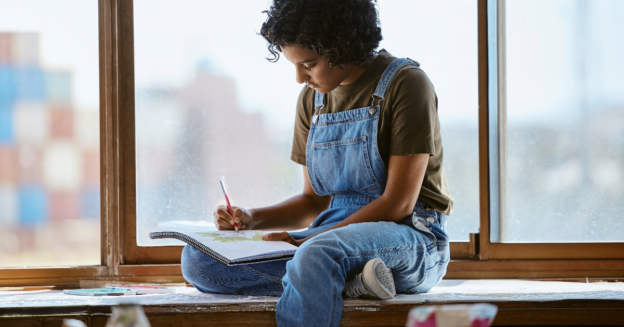

Pencil in Hand

“You hear of those children who were, so to speak, born with a drawing pencil in their hand,” says Angeloch. “Well, that was me! Both of my parents and my grandparents on my mother’s side were artists. In fact, upon entering elementary school, I was surprised to learn that other kids’ parents did other things besides art.”

Growing up the son of noted artists, however, was not always easy, especially in regard to his father, celebrated artist and co-founder of the acclaimed Woodstock School of Art, Robert Angeloch (1922–2011). He reflects, “Growing up in a world of art was very beneficial, although I somehow felt my father and I were in competition.”

The Power of Simplicity

Seeking to find his own way, Angeloch studied for a year at the Art Students League of New York with Robert Hale and Stephen Greene. Angeloch returned to Woodstock to paint and to assist his father in printing his serigraphs. Upon turning 40 in the year 2000, Angeloch determined that it was time to reassess. “I decided to give this painting thing another go and try to simplify everything.”

At one point, he remembered an exercise his father had him do with a limited palette. So, he thought limiting his palette was a good place to start. He used only raw umber, burnt umber, ivory black, and titanium white. “That worked well for a while,” says Angeloch. “Gradually I expanded, adding colors in the primaries of slightly higher intensities: yellow ochre, burnt sienna, and Payne’s gray. I add cadmium yellow light and cadmium yellow dark for those times when I need to achieve more intense greens. These colors can be used transparently and opaquely. And if I juxtapose them correctly, they can take on a greater feeling of intensity. It’s all about placement and the interaction of color.”

Intuition & Experimentation

Angeloch cites William Blake who said, “The true method of knowledge is experiment,” when Angeloch describes his own approach to advancement and discovery in the painting process. “As a result of printing dozens of serigraph editions for my father, my method is technically derivative of the silkscreen process in which each step has to be the final step of that process. There’s no going back in silkscreen. You get it right the first time. So instead of blocking-in big areas and then whittling them down to smaller shapes, I use numerous layers of thin paint in flat applications of color.

“I build form and texture, layer by layer and light to dark, letting each coat dry before proceeding to the next. The greatest difference is that while serigraph imagery is carefully planned, I’m intuitive. That’s one of two constants in my work. The other is experimentation.”

The Most Satisfying Medium

“For my purposes, alkyd is the most satisfying medium I’ve worked with,” says Angeloch. To hasten drying times, the artist often works smaller-sized paintings on gessoed paper mounted to a board. At times, he adds a small amount of Liquin into the paint. For these works, Strathmore serigraph printing paper is his favorite surface. Angeloch paints larger paintings, for practical purposes, on Fredrix Ultra Smooth PolyFlax/ cotton blend canvas.

Why Alkyds? Alkyds consist of pigments in an emulsion of linseed oil and alcohol, and have all the properties of traditional oils but with a quicker drying time. They’re important for artists, like Angeloch, who work indirectly, utilizing numerous layers of thin paint.

Painting from Within

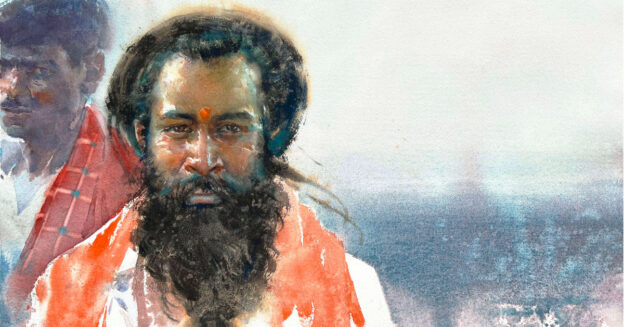

For nearly a decade and a half, Angeloch has been painting images conjured solely from his memory and imagination. “I have no preconceived ideas when I go into these things,” says Angeloch. “I let the interaction of what’s inside of me and the canvas develop of its own accord.” Landscape is a subject he knows well; this stems from his long walks, by day and night, in the natural beauty of the Catskill landscape and beyond.

“When I observe the landscape in the moment, I feel something deeper than I do at any other time. I attain a sense of connectivity — a oneness with nature that’s hard to explain,” he says.

The Qualities of Mood

The qualities of mood have come so much to the forefront of his expression that the artist begins by painting the sky to near completion. For this artist, hands down, it’s the sky that conveys the all-important mood or feeling and that dictates the remainder of the work. After the sky is resolved, meaning about 95 percent or more of the painting is finished, Angeloch works from the background to the foreground, creating distant features such as mountains, hills, or tree lines before painting foreground elements.

Throughout this process, simplicity is key. “I always try to keep my pictures as simplified as possible,” he says. “While conveying subtleties of texture and volume to the degree necessary to achieve a satisfying end result.” From Maple Avenue, East shows how the artist can strip a landscape of any significant topographical features which, in the artist’s own words, “impart a sense of placidity — a mood I frequently wish to convey.”

At the same time, he unmistakably creates a dynamic tension between that stable, calm stretch of field and the unstable, unsettled sky above. “This turbulent mood, coupled with the implied movement in the sky over that stillness of flat, once-farmed fields, provides a contrast that would’ve been lacking if the scene depicted a calm, blue-sky day,” says Angeloch.

Imagination at Work

The Space Between is created entirely from the artist’s imagination. In its previous life it had a dark sky and a grouping of trees behind the large tree on the left. When it was returned from a gallery showing, Angeloch felt he could both simplify the work and express a different mood. The result, so skillful in draftsmanship, is a testimonial to an elegant resolution of the formal elements of painting and appears timeless in its beauty.

“I spend a lot of time looking at the sky,” says Angeloch. “It speaks louder to me than any other landscape element. I find it’s essential to pay attention to the cloud edges in order to maintain their softness as they float, constantly changing, above the landscape.”

The atmospheric, dreamlike quality in Summer in the Catskills transposes the substance of an iconic image into matter, both familiar and strange, which seems to oscillate between the real, the recollected, and the imagined.

Painting Intuitively

Moon Over Bearsville 1 represents a distinct direction in Angeloch’s painting. “When I began, I had no idea that it was going to be a night scene or that there wouldn’t be land or even that there would be a moon,” he says. “The painting was very dark gray and it evolved from there. Since I’m an intuitive painter, I have to trust in the action of painting. Every moment ventures into unchartered territory.”

While painting Moon Over Bearsville 1, he thought of putting in trees, but when the night sky was finished, he liked it and thought it was complete as is. Moon Over Bearsville 2 followed, and he discovered that this painting works well shown from any side. Accordingly, he attached four wires and encouraged his gallery director to change its orientation on occasion. These sky paintings, like his landscapes, readily invite reflection.

Angeloch’s paintings preserve for the viewer a characteristic, uncommon quiet that’s as much born of idea, of meditation, as it is of perception plus paint applied with sensitive mastery. Referring to the two night sky paintings, Angeloch says, “Observing the sky as much as I do invariably leads me to paint it devoid of any other landscape elements. I’ve found people have emotional responses to these works, running the gamut from serenity to excitement. What more could one ask for?”

Demo: 9 Steps Toward Translucence

In the following demonstration, Eric Angeloch shares his process for creating the illusion of semitransparent light in landscapes.

1. Prepare paper

I began by preparing a piece of serigraph printing paper with gesso. Then, over the top two-thirds of the paper, I applied a light-valued mixture of raw umber, titanium white and a small amount of Liquin and then another mixture, ivory black, titanium white, and Liquin, was applied over the first, leaving some parts of the previous layer untouched so I could determine the light side of the clouds. It’s vital that the painting dries between each stage.

2. Create the sky

I then made a mixture of Liquin, Payne’s gray and titanium white — roughly the same value as the white/black mixture, which served as the “blue” of the sky. The mixture had to be opaque enough to obscure parts of the first layer without experiencing any bleed through.

3. Accentuate shapes

I wanted to accentuate the cloud shapes by adding highlights with titanium white and raw umber. I used 1⁄4-inch nylon filbert for good control. Next, I made a medium- valued mixture of titanium white and ivory black. Using the same brush, I indicated a distant row of trees. Note that no Liquin was used in this step.

4. Add texture

I made another, slightly darker, mixture from titanium white and ivory black to indicate a closer row of trees. Next, I added a little more ivory black to the existing mixture and switched to a small hog-hair filbert, allowing me to apply the paint in a more broken manner to indicate the tree texture.

5. Vary viscosity

Translucent paint allows for more light to pass through, achieving effects similar to those found in many watercolor paintings. Here, I mixed five parts yellow ochre with one part ivory black to produce a light-valued yellow/green. To this, I slowly added Liquin until the resulting mixture took on a translucent quality; using a large nylon filbert, I applied the mixture to the bot- tom third of the painting.

Then I returned to the translucent mixture and added a little more ivory black, making the mixture a darker value. Using a smaller filbert, I painted into the existing wet layer of paint, selectively; I was sure to leave about half of the initial green mixture untouched. I then made another mixture of five parts yellow ochre and one part ivory black; then I added just enough Liquin to allow the paint to flow, yet retain its opaque state. Using the small hog-hair filbert, I applied this onto the wet surface sparingly in order to develop a sense of visual texture and a subtle variation of hue.

I added a little more ivory black to the mixture and repeated its careful application.

6. Create value

In order to determine the light sides of the trees, I added a light-valued green with a mixture of two-thirds ivory black and one-third cadmium yellow deep. To this, I added titanium white until there was a distinct difference in value from the tree line. Using a small nylon filbert, I added bits of the mixture, primarily at the tops of the trees and along the left sides. Rather than stroking the paint onto the picture, I used the tip of the brush and used a stippling technique in order to enhance visual texture.

7. Work on the foreground

Here, I developed the field by making different greens with cadmium yellow light, cadmium yellow deep, Payne’s gray and ivory black. Remember, cooler greens recede and warmer, more intense greens, move forward. Apply these mixtures sparingly — this step is easily overworked. Use the brush with which you feel most comfortable. I like the small hog-hair filbert.

My paintings are not preconceived; they evolve as I progress. It was at this stage that I committed to the idea of adding a stream into the picture.

8. Develop the stream

I indicated the stream by applying a mixture of titanium white and ivory black in a light to middle value. Furthest away, I used the small nylon filbert and painted in an unbroken, opaque manner. As I moved toward the foreground, I painted in a more broken manner. Then, I lightened the mixture by adding more titanium white and, using a Winsor & Newton Series 7 round, size 0, made a few short strokes where the edges of water and land meet.

9. Accomplish final touch-ups

Everything was now in place. I added some lighter-valued mixtures to the trees and a few more highlights to the clouds. I applied in a broken manner a mixture of raw umber and titanium white to create highlights in the water, and applied a light yellow/gray mix to the foreground to create visual texture and a sense of detail.

Learn more about Eric Angeloch and see more of his work at ericangeloch.com.

A version of this article originally appeared in Artists Magazine.

Join the Conversation!