Your First Successful Watercolor Painting Starts Here

Beginner Watercolor: All About the Paints

Selecting a palette of colors often means limiting the choices, making studies and experimenting along the way. One of the keys to being successful as a beginner watercolor artist is to choose a workable set of colors.

Delve into what your palette can be and then start experimenting. Success is a guarantee — because your success is about experimenting and having fun, artists!

And if you are ready for your next step in watercolor, Painting from Photographs in Watercolor with Jo Beth Gilliam is the video download for you. It equips you with how to use photographs as references to get a beautiful painting while avoiding all the problems artists often face when they use photos the wrong way. Enjoy!

Limit Your Colors — Or Not

With the wide range of watercolors available, there is no particular reason to limit a palette to only primary and secondary colors. In fact, taking advantage of all the variations can save time.

On the other hand, artists will sometimes limit the colors for a single painting or over time will discover preferences. And these color decisions help to determine an artist’s unique style or approach.

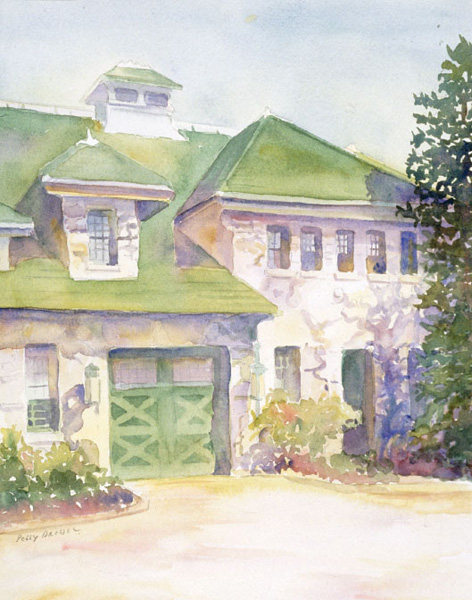

“Buying every tube of paint out there is unrealistic for a couple of reasons,” says Peggy Dressel, an artist and teacher in Oakland, New Jersey. “Palettes have just so many openings, and I want to limit my colors to one palette. Also, I don’t need to duplicate paints that have different names but are very close in color.”

Dressel suggests a two-pronged approach to choosing a palette of colors. First, she recommends her students consider what they want to paint.

“Although I want my colors to span the color wheel, if I’m painting flowers, I know there are pinks and purples in the translucent flower petals that I can’t mix with my basic palette. In this instance, I will add transparent pinks and purples to the palette,” she explains. “If I’m going to paint the landscape, I will consider adding more earth tones. I call these specialized palettes, because I’ve modified them based on subject matter.”

Her second recommendation is to choose a warm and cool version of each hue. By this, Dressel means she chooses two versions of a single hue that are tinged with colors framing it on the color wheel. For example, she chooses a warm orangish yellow and a cool greenish yellow or a reddish purple and a bluish purple. This allows her more ease in mixing without worrying about the muddying from color tinges.

As a final step, she includes earth colors, both transparent and opaque, and a few granulation colors. In some cases, certain color mixtures enhance the granulation, such as French ultramarine and burnt sienna, and she uses this to her advantage.

Dressel’s Basic Palette

Dressel has selected several colors that form her standard palette. Each one makes a valuable contribution.

Reds, Oranges, and Yellows

- Cadmium red deep: “This is a middle red color leaning slightly toward yellow, so I consider it warm. I don’t use it as much as I used to, but I will still turn to it when painting portraits because it’s slightly opaque. It doesn’t mix well with blues because it has yellow in it.”

- Winsor red deep: “This is a middle red with a yellowish tinge that is very transparent. It has replaced the cadmium red on my palette.”

- Permanent alizarin crimson: “I use the Winsor & Newton. It’s a slightly bluish, cool, dark red. There was a debate about whether alizarin crimson was lightfast, so I replaced it with the permanent version, which is pinker and brighter.”

- Cadmium orange: “A color that can range from a yellowish to a reddish orange. More often I mix new gamboge with reds to obtain my oranges.”

- Lemon yellow: “Lemon yellow is the only cool yellow. I’m not that crazy about it because it’s usually very chalky. I use it when painting something absolutely yellow where I need a cooler part and don’t want to add green.”

- Aureolin: “I love this yellow. It’s a bright transparent yellow that I consider a neutral color, meaning it mixes with anything.”

- Winsor yellow: “It is very transparent. The color is almost the same as aureolin, but it’s very intense.”

- New gamboge: “It’s a warm, almost orange-yellow, and very translucent.”

Greens and Blues

Viridian: “This is a cool, delicate transparent green that looks very unnatural, and most students don’t like it. It’s the most versatile green on the palette, however, and it mixes well to form a range of warm and cool greens.”

Viridian: “This is a cool, delicate transparent green that looks very unnatural, and most students don’t like it. It’s the most versatile green on the palette, however, and it mixes well to form a range of warm and cool greens.”- Winsor green (blue shade): “It is similar to the viridian, but it’s stronger and can’t be used alone. It’s better to use in darker mixtures. It makes a black when mixed with almost any red.

- Winsor green (yellow shade): Like Winsor green (blue shade), this is very intense. I mix it with oranges to obtain a sap yellow, and it gives a dark green when mixed with burnt sienna. I tried to use this instead of Hooker’s green but found it warmer, so it’s not been an entirely successful substitution.”

- Hooker’s green: “I like this color because it’s dark, yellowish, and transparent. There are two versions, and I have the warmer version. It mixes well with reds, blues, and burnt sienna. There was some debate about its lightfastness, so although I have it on my palette, I don’t use it as much as I used to.”

- Sap green: “A warm green that is perfect for beginner watercolor art pieces. Artists love to use it straight out of the tube. I think it should be somewhat mixed. It mixes particularly well with French ultramarine for a dark green.”

- Cobalt blue: “I use the Holbein cobalt blue. To me this is the closest to a pure blue that’s possible with paint. I use it for a lot of skies and shading white objects.”

- French ultramarine: “It’s a dark yet bright blue, and it contains a great deal of red. For that reason I consider it a warm blue. It works great with alizarin crimson for beautiful purples, but for good greens it doesn’t work. What I’ve found, however, is when painting trees at night, French ultramarine mixed with yellow instantly gives the exact muted green I’m after.”

- Winsor blue (red shade): “This is a warm blue. I was trying to use this instead of French ultramarine in areas containing dark water, and I found it worked very well. It’s good for mixing purples.”

- Winsor blue (green shade): “This is similar to the Holbein peacock blue. If you try to mix a yellow with it, you get a wonderful variety of greens. Both these colors are good examples of how the color tinges affect mixtures.”

- Prussian blue:“This is a dark, strong-valued color. I replaced my indigo with it because I found the indigo had too much black in it. The Prussian is also tinged with green, so I consider it a cool blue.”

- Cerulean blue: “It is slightly opaque and cool, and it’s good for skies.”

More Color Options

Permanent rose: “I substituted this for rose madder, which I was told was not lightfast. I prefer the permanent rose because it’s brighter and pinker. Another pink I sometimes use is Holbein’s opera, which is now said to be permanent.”

Permanent rose: “I substituted this for rose madder, which I was told was not lightfast. I prefer the permanent rose because it’s brighter and pinker. Another pink I sometimes use is Holbein’s opera, which is now said to be permanent.”

Winsor violet: “This is somewhat in the middle of the purple/violet range.”

Raw sienna, burnt sienna and Daniel Smith quinacridone sienna form Dressel’s earth tones, along with quinacridone gold.

“Quinacridone gold is getting very popular,” says Dressel. “It is transparent and makes great transparent greens when mixed with blue. It works well for landscapes, and when added to trees and rocks it really holds the picture together.

She continues, “Originally many landscape painters used a triad of French ultramarine, burnt sienna, and raw sienna or yellow ochre. But that combination wasn’t translucent. The quinacridones came out, and these colors are changing the outlook of watercolor painting because they are making it possible to get more vibrancy in landscape paintings.”

For preliminary value studies, the artist uses ivory black; but the color never enters a finished painting. White is also banned.

“I know sets include Chinese white, and the first question asked by students is why we’re not using it,” says Dressel. “Of course there is no one way to do watercolor, and many beautiful watercolors have been made with mixtures of white, but since white is opaque, I don’t use it.”

Testing Colors Before Painting

Not every color will enter every painting Dressel undertakes. In beginner watercolor painting, that is something to be especially aware of — you don’t have to use all the colors on your palette. In fact, Dressel says she frequently limits her colors to create color harmony.

Before beginning a painting she tests her limited colors. “I choose a triad of primary colors — a specific red, yellow and blue — and then I mix them together and place them as though creating a color wheel,” explains Dressel.

She may choose this triad from the colors on her palette, or she may look to her subject for colors to use as a starting point. “I choose a triad of red, yellow, and blue that I see fits the subject, and I mix these colors around the wheel. This shows me the type of oranges, purples and greens available from that triad. I usually do more than one, always remembering to write down the specific colors in each triad,” she says.

Dressel adds, “Once I choose a particular primary triad, I can look and decide what colors I need to add to that particular palette. I may need a better orange, so I will add a pure orange rather than mix one. If I’m going to be painting a lot of very light areas, I will start with a light triad and supplement with a darker triad.”

Exercises to Get Color Right

“I suggest painting a picture with these colors,” recommends Dressel. “Then make a new triad by substituting the blue you have with another blue and repeat the process to see how the color mixtures differ. If you normally use French ultramarine and you think you’d like more transparency, try Winsor blue (red shade). It appears to be the same color, but you have to mix it with the other colors to see how the results differ.”

Finally, Dressel photocopies a 5- by 7-inch sketch, upon which she does both a value study in ivory black and color studies to work out the color composition. She then hangs the one that appeals to her most on the wall as a reference when working on the final painting.

“Doing the studies will save time in the long run,” she says. “If I spend 20 minutes prethinking my colors, it will possibly save me from having to redo the entire picture at a later point, and it will improve the result.”

Now that you have absorbed all of these beginner watercolor tips you can start working on your best painting yet!

*Article contributions by Christopher Willard

Have a technical question?

Contact UsJoin the Conversation!