Beginner Drawing Logic: Getting Depth Into Your Drawings

Here are some ways to give depth to your drawings.

Here are some ways to give depth to your drawings.

by Bob Bahr

A sense of depth makes a drawing much more convincing. The Old Masters used a number of devices to give depth to their drawings and paintings. Here are a few.

Vermeer is just one artist who effectively used repoussoir to create the illusion of depth in his art. â??Repoussoirâ? is a French verb meaning â??to push back,â? and in drawing compositions this often means placing a large figure or another prominent element in the extreme foregroundâ??often on the left, where it is quickly read by viewers as their eyes scan from left to right, moving on quickly to the focal point after having instantly registered the sense of depth suggested. In Vermeerâ??s The Artistâ??s Studio, for example, the artist uses a curtain on the left to create the sense of space.

Obviously, repoussoirâ??s success is attributable to the fact that objects lessen in size the farther they are from the viewer. But many drawing problems in compositions are attributable to issues of scale stemming from this evident physical law. Careful attention to the rules of perspective will ensure that objects are diminishing in size at the proper rate as they recede into the distance.

Objects in the distance are also lighter, less defined, and seem more tightly clustered than similar objects in the middle ground and foreground. Elements appear lighter and less detailed because light, the vehicle for visual information, is affected by Earthâ??s atmosphere. Even under very clear conditions, light (and thus, the appearance of all distant objects) is altered by the optical phenomenon known as Rayleigh scattering. The more atmosphere between the viewer and the object, the more pronounced the effect. Named after Lord Rayleigh, the 19th-century physicist who discovered it, this effect is caused by particles in the air that are smaller in size than a wavelength of light, thus scattering or defusing the light. (Incidentally, the smaller the wavelength of light, the more it is scattered, which explains how our eyes interpret the blue of the sky. The skyâ??s blue color is caused by sunlight scattering off molecules of the atmosphere. Because blue light has a very short wavelength, it is scattered more readily, and thus blue light is more visible in our atmosphere.) Light is further diffused by larger particles, such as those of smoke, pollution, and fog, and the effect of these factors (called Mie scattering after German physicist Gustav Mie) is more pronounced closer to the horizon than at the zenith of the sky because these heavier particles sink closer to the ground.

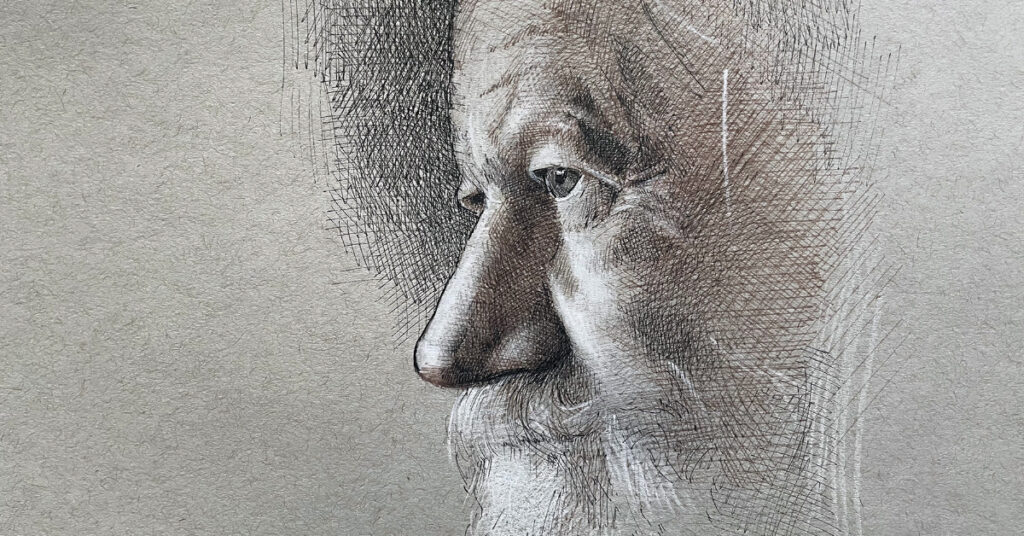

Artists refer to this overall phenomenon as aerial (or atmospheric) perspective, which is confusing because it has nothing to do with perspective of scale, the usual meaning of the term perspective in discussions of art and composition. (None other than Leonardo gave aerial perspective its name, which probably has something to do with its perseverance.) To suggest the effect of aerial perspective caused by the atmosphere, make the contrasts in value in objects less defined in the far distance. That is, draw features in objects in the distance using marks that are close in value. The atmosphere also softens and blurs the contours of distant objects a little bitâ??but keep in mind that the main reason their edges are less noticeable is because of the reduction in contrast between their light and dark planes. The important thing is to lighten their tone overall in comparison to similar objects in the middle ground and foreground.

When working in color, incorporate blue into the hue of the colors in the background to reinforce the Rayleigh scattering effect. (Pollution and smoke, through Mie scattering, may mean altering the overall tone not with blue but with a warm color.) And remember that shadows in the distance are affected by the same physical laws as other objects in the distanceâ??that is, shadows in the background should be lighter than shadows in the foreground.

Another very helpful way to imply depth in a drawing is to overlap elements according to the logic of the scene. Adding a branch to a middle-ground tree that overlaps a building in the background will help push the building back. Distant mountains at different depths should overlap so the difference in their tone is readily apparent. Even if they donâ??t overlap in the actual scene, this adjustment should be considered on your paper anyway.

And finally, the human figure, an object that everyone inherently knows well, can be placed at the appropriate scale anywhere in the composition to create an instant understanding of the depth implied in the composition.

If you would like more information for Beginner Drawing: Download our free ebook: Step by Step Draw People from a Photograph: 31 Tips on How to draw people from a photograph

Like what you read? Become a Drawing subscriber today!

Have a technical question?

Contact UsJoin the Conversation!