Working the Roots: The Landscapes of Macario Pascual

The landscapes of artist Macario Pascual bring color and attention to the story of immigrants and laborers in Hawaii’s sugarcane fields.

My son leans in to watch Macario Pascual bait two hooks with pieces of shrimp. He then walks with him to the edge of a concrete pier overlooking the Hana Harbor on the remote eastern shore of Maui. “Just let it hit the bottom and then reel it in a little,” Pascual explains, demonstrating before handing off the pole. My sons have fished the trout streams of Montana, but never the deep waters of the Pacific. They stare into the dark waters expectantly, wondering what lies beneath.

oil on panel, 18×24

Towering slate gray clouds, carried by trade winds, drift in from the open ocean. Bright sweeps of rain dissolve the horizon and drift toward us. Behind us, the clouds stack up against the towering hulk of Haleakalā and deposit rain in abundance. Fashioned by twin volcanoes joined at the hip by an isthmus, Maui is home to a wide range of climates, from rainforest to desert, all packed into an area only two-thirds the size of Rhode Island.

Subscribe to Artists Magazine now so you don’t miss any great art instruction, inspiration, and articles like this one.

We’d hoped to squeeze in another painting session together before the artist (and fisherman) returned to his home in Lahaina, a seaside town on the leeward side of the West Maui Mountains. Instead, we sit on the pier with my wife and talk about his experiences growing up on the island—and its impact on his painting. A turtle rises to the surface before diving back down to feed on the reef.

oil on panel, 36×48

A New World

In 2016, the last sugar mill in Hawaii closed after 115 years in operation, marking the end of a rich chapter in the cultural history of Maui. All that remains is the shell of a mill and the great smokestack overlooking Lahaina. It’s August, and in contrast to the verdant lushness of Hana, the west side of Maui is bone dry. The hillsides along the slopes of the West Maui Mountains and along the leeward flanks of Haleakalā—once a colorful tapestry of irrigated fields—are bleached and barren. There’s talk of replacement crops, hemp perhaps, but for now the fields are fallow.

It was the promise of work on the sugarcane plantations that lured Pascual’s father from the Philippines to Maui shortly after World War II. He signed on as a contract laborer, a sakadas, as they were called, meaning “newcomers.” He was among the last wave of Filipino immigrants to arrive on the island. For nearly a decade, he worked long days under the tropical sun alongside native Hawaiians and immigrants from Japan, China, Puerto Rico, Portugal and Scotland.

In 1955, during a visit to the Philippines, Pascual’s father married. A year later, he and his new wife welcomed the arrival of a baby boy. With steady work on one of the many sugar plantations and scant prospects for betterment in the small farming village in the Philippines, he petitioned to have his new wife and son join him in Maui. In 1962, Pascual, a wide-eyed child of five, started his new life on the most far-flung chain of islands on the planet.

oil on panel, 45 x 341/2

A Future in Art

Pascual remembers his childhood fondly. “No one locked the door, and everyone knew each other,” he says. “It didn’t matter if you were Filipino, Japanese or Hawaiian, if there was a party, everyone was invited. It truly was a melting pot.”

Initially, Pascual struggled with the transition to a new country, and—faced with language and cultural barriers—he retreated into art. “Eventually, my drawing attracted other students to me,” he recalls, and as he overcame the language barrier, he started to make friends.

“I SAW THE LIFE OF THE SUGAR

—MAC ARIO PASCUAL

CANE WORKERS EVERY DAY.

MY DAD, MY NEIGHBORS—

THEY LIVED IT.”

Pascual’s route home from school took him past the shared studio of two artists. They eventually invited him in to paint with them. They provided a space for him to work and generously shared both their knowledge and materials. That summer, he made $500 selling his paintings at the local park—“pretty good money for 1969,” Pascual notes.

In that summer he saw his future, and that future was in art. That is, until his father secured a special permit for him to work on a pineapple plantation for the summer. “My mom cried. She was so mad!” he laughs, shaking his head in bemusement. Pascual had no idea the tension his father’s decision had caused. “He just wanted me to know the value of a dollar,” he explains. She saw only the backbreaking labor from which they’d worked so hard to spare their son. Eventually, she relented, and Pascual went to work in the fields. “I worked primarily in a ‘Hoe Hana’ gang, hoeing the weeds and tall grasses that dotted the endless rows of pineapple plants.” While it seemed like a temporary detour on the road to becoming an artist, his experiences that summer would eventually figure into his art in significant ways.

In 1974, Pascual attended the University of Hawaii on an athletic scholarship. There he devoted his time to painting and tennis, his two great loves. Then, during his sophomore year, he was commissioned by the state to do a series of paintings commemorating the arrival of Filipino immigrants to the state in the early 20th century. The project marked a turning point in his life.

“I rediscovered my roots,” he explains. “Up to that time, I’d wanted to be more American. I then realized there’s nothing wrong with me or where I came from. I felt proud.” The experience helped the artist see in a new light his family and his story, including that summer of hoeing for the Maui Land and Pine as a teenager. “I realized no one had painted the laborers and the immigrant experience of Maui.”

Despite the advice of galleries to paint beaches and seascapes, Pascual felt he wasn’t done painting the sugarcane plantations. He approached the Royal Lahaina Art Society with the idea of a show, and to his surprise, it gave him the green light. “I didn’t know if it was something people would be interested in,” he recalls, and he wondered if he’d sell a single painting. “It was just something I felt I needed to do,” he says. “I saw the life of the sugarcane workers every day. My dad, my neighbors—they lived it.” He felt it was a story worth telling. As it turned out, the show was a huge success. “I sold a lot of paintings, and that just got me going.”

oil on panel, 36×48

Facing Headwinds

In 1995, the economy was soft, and Pascual felt the hit. He had a mortgage and a young family, and Hurricane Iniki had leveled the island of Kaua`i, including a gallery that represented his work. “I just couldn’t let it go,” he recalls. So, he looked for ways to trim the fat. He gave up his studio gallery and evaluated his material costs. “I had a palette of 13 or 14 colors, and I thought, ‘What if I just kept three or four colors?’ Paint is expensive!” So, he limited his palette to alizarin crimson, cadmium yellow light, veridian, and titanium white. He wistfully calls it “my starved palette.”

Far from being a limitation in his work, the change actually re-energized him. “When I limited my palette,” he says, “I discovered I could mix my own colors according to my own sensibilities.” What at first seemed to be a constraint now fueled artistic growth. “Colors are like friends,” Pascual says. “You can have 100 friends, but you don’t know much about them. If you have three or four, you know everything about them.” In scarcity, he was revitalized.

In 2013, Pascual was invited to lunch with Sue Cooley, an avid collector and philanthropist, and Lynn Shue, owner of the Village Gallery, in Lahaina, with whom Pascual had worked for many years. To his shock, they offered him a $13,000 grant with no stipulations. “Do the paintings you really care about,” Cooley said simply. Over the year, Pascual worked up 12 large paintings and, with the help of Shue, arranged an exhibition at the Ritz Carlton in Kapalua.

Over the previous decade, he’d focused mostly on pure landscapes, inspired by his experiences with other artists during the Maui Plein Air Painting Invitational. He participated in the festival for its first 11 years, since its inception in 2006. His interactions over the years with other artists there acted as something of a refresher course. “We might talk about color temperature or blurred edges or seeing a scene in terms of shapes and patterns,” he says. “I know what these things are, but I’d never heard it expressed quite like that.” It connected him to the Maui landscape on a deeper level, and it got the artist excited to try new techniques.

oil on panel, 40×30

oil on panel, 32×24

A Story Worth Telling

The resulting show, entitled “Roots—Plantation Life Revisited,” was a culmination of decades of artistic growth, combining Pascual’s mastery of the landscape, his exquisite color sense and the timeless stories of plantation life into 12 large paintings.

Peruse the series, and you’ll find two extremes: At one end, the landscape dominates; at the other, the figure dominates. In Big Valley (page 42), evening light floods the grassy slopes of the West Maui Mountains in green and rose, and casts serpentine blue shadows along the deep fissures. In the foreground, nearly lost in lavender shadows, the workers toil, loading carts with freshly cut sugarcane. The inspiration for the landscape came in a brief moment of evening light during a lush, wet summer. Pascual recorded, on-site, what he could in the fleeting moments before the clouds eclipsed the evening light.

“I tried to visualize what it was like back in the day at this very spot when sugar was king,” he explains. “Imagine working as a harvester with long hours of hard labor for a few bucks a day. According to my dad, who once worked hapai ko [to carry cane], it was the most grueling and miserable job in the industry. It left him tired, sore and covered with ash by day’s end.” The painting combines breathless beauty and backbreaking labor in one thought-provoking tableau.

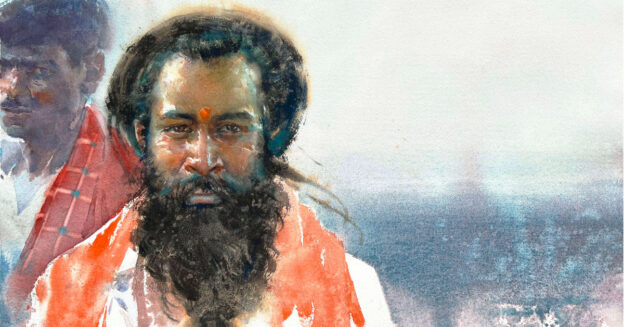

In other paintings, such as Worker in Light and Cut Cane and Tattered Hat, the artist focuses on the figure—solitary workers surrounded by tall stacks of cane, absorbed in the rhythms of work. Their identities are often hidden beneath straw hats and layers of protective clothing as they bend to cut and stack the sugarcane. Pascual doesn’t editorialize or romanticize; he simply presents the workers in what is, to us, an exotic environment. In seeing these figures—in the gesture of their work and sweep of sugarcane stalks—a viewer might be reminded of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) paintings of the 1930s or even of the Greco-Roman friezes of antiquity.

Within four years after his exhibition, laborers for Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar gathered the last sugarcane harvest on Maui. All that’s left is the great smokestacks (see Early Light/Final Harvest, opposite) and a scattering of equipment—relics of a proud industry that once attracted immigrants from across the world. The life of the mill and the voices of the immigrant workers live on in Pascual’s paintings.

oil on panel, 12×16

Past, Present, Future

In order to mine the past, Pascual looks to the future. He’d like to work with the younger generation to learn the stories of the previous one. “I realize that some of the kids that I meet were born after the mill shut down,” he explains. “This is their legacy, their heritage. There are bound to be boxes of photos in the homes of their parents,” he says. “I’d love to paint from them. I’ve done paintings of workers in the field, but I’ve never focused on who these people were at home.”

Far from being discouraged by the end of an era, the artist is inspired to unpack the stories and find new subjects to paint. After all, the story of his father—a Filipino immigrant looking for a better life and working for the future of his children—is the quintessential American story. Mix his story with the stories of native Hawaiians—as well as the Japanese, Chinese and Scottish immigrants, and others who came to the Hawaiian islands—and a unique, complex, sometimes troubling but often inspiring narrative emerges.

A Human Story

As I sit on the pier with Pascual and my wife and consider the stories that fill his paintings, we’re suddenly interrupted from our reverie. “I got one!” shouts my son, and Pascual jumps into action. It’s a strange fish—gray with yellow fins, a backward-pointing horn on top of its head, and human-looking teeth. Pascual picks up a towel and pliers. “You don’t want to grab it with bare hands,” he explains. As they reel it in, it strikes me that this, too, is the American story—a Filipino immigrant helping the great-great-grandson of Norwegian immigrants land a strange ocean fish. On some level, we’re all aliens here; on another, we all belong. Each one of us contributes to a story that’s greater than any one individual—a story that will outlast us all. Pascual’s paintings bring a visual picture to one fascinating part of this larger tale.

Based in Livingston, Montana, Aaron Schuerr is a landscape painter and plein air enthusiast and a frequent contributing writer to art publications.

Enjoying this article? Sign up for our newsletter!

From Our Shop

Do you have any updates on this incredible artist after the tragic fires that destroyed Lahaina?