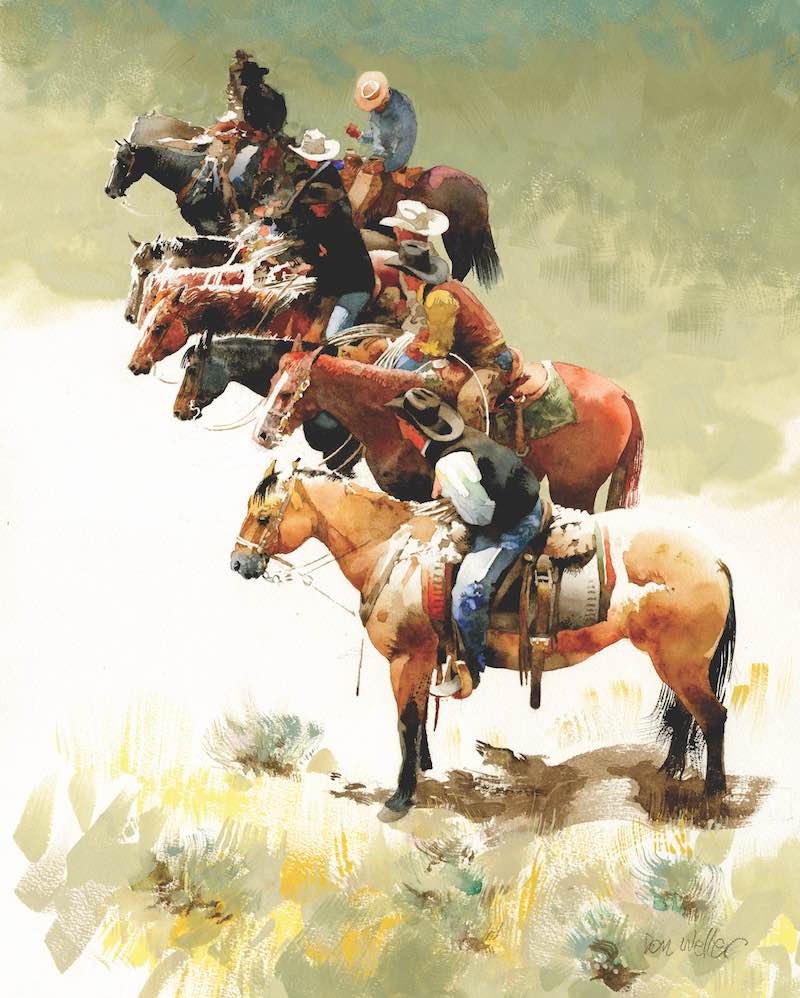

Don Weller: Of Horses and Humans

Renowned artist Don Weller brings the Western world of the contemporary cowboy to life.

This article originally appeared in Watercolor Artists Magazine. Subscribe now so you don’t miss any great art instruction, inspiration, and articles like this one.

Some ranchers today may round up cattle using four-wheelers, but in the world of Utah artist Don Weller, you’ll find plenty of cowboys on horseback. His watercolor paintings are proof, each one energized with sparkling color and a dynamic composition. “I was raised in the American West, and it’s what I know,” he says. He grew up in Pullman, Wash., in the eastern part of the state, surrounded by wheat fields, rolling hills and the Palouse River.

It was in that bucolic setting that Weller’s affinity for cowboys and horses was born. “Once my brother and I were old enough to go to the Saturday matinees alone to watch Westerns, I began my search for cowboys,” he says. He drew the humans and horses on paper and longed to experience life in the saddle firsthand. “My whining to my parents finally paid off,” he notes, “when I got my own horse.”

Exploring the western terrain on horseback was an exhilarating adventure, one that enabled Weller to experience the symbiotic bond between rider and horse, as well as to develop a deep appreciation for the beauty of the rugged outdoors. He’d often sketch while in the saddle. Weller’s ongoing fascination with horses eventually led him to the worlds of calf roping and rodeo competitions in high school and young adulthood. Today, at the age of 86, one of Weller’s favorite activities is working his three “cutting” horses—horses that are adept at splitting off a single cow from the herd.

So, how did Weller go from riding horses to a successful career depicting those four-legged creatures and their hardworking riders in artwork? Like most stories told around the campfire, it was a circuitous route for the hero.

Weller attended Washington State University without a clear idea of what he wanted to do. An elective class in life drawing changed that. “My major was fine art, which in those days meant Abstract Expressionism,” he says. “What stuck was the knowledge that ideas could be important—and how to draw and stretch watercolor paper.” He went on to earn his bachelor’s degree in fine art.

After a stint with the Air National Guard, in Texas, Weller went looking for work in Los Angeles. There, he learned the business of graphic design by working with a number of design studios. He eventually opened his own one-man shop and for decades did graphic design and illustration, enjoying relationships with clients such as TIME magazine, the National Football League and the U.S. Postal Service, for which he designed five stamps.

During this time, Weller also taught art part-time – three years at UCLA beginning in 1967 – where he met his wife, Chikako “Cha Cha” Matsubayashi, and 11 years at the ArtCenter College of Design. In 1984, realizing he had seen all the cement and palm trees he could stand, he and Cha Cha moved to Utah, where he taught at Brigham Young University and the University of Utah; he retired from teaching about 15 years ago.

The move to Utah, just east of Salt Lake City and at the edge of the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest, freed Weller from the city and was a literal breath of fresh air. “The rural West with mountains, sagebrush and cowboys—it was still there, just as I had left it so long ago,” he says.

Weller once again found himself traversing the American West, this time painting lyrically romantic works featuring Native Americans and cowboys, horses and cows, rodeos and rough-stock, bronc riding and roping, barrel racing and branding, bulls and buffalo, and more.

A Studio Built for Two (Media)

The couple built their Utah house in 1994, and it features a large studio. Weller, who served as the architect,

says, “My dad had been an architect, so I knew how to do the drawings the old-fashioned way, with tracing paper and pencils.” The property includes a barn with several stalls for the all-important horses, as well as a garage, which houses his second-floor studio with two distinct areas: one for his work in watercolor; the other for oil painting, which he recently has picked up again. “I try to keep the two media separate,” he says, “because oils are so messy, take forever to dry and ruin my clothes.”

For his watercolor practice, Weller has set up a drafting table that can be tilted to help him control paint washes. Additionally, he has flat files for paper and finished works, as well as an abundance of flat surfaces for watercolor palettes, brushes and cans. “Visually, it’s a mess,” he says of the much-used working space. While the studio offers natural light conducive to painting in both media, Weller has supplemented it with more artificial light sources over time to compensate for his worsening eyesight from macular degeneration.

Blazing the Artistic Trail

Although Weller has spent a lifetime filling sketchbooks on-site, these days he prefers to work from printed photos. When out looking for subject matter on horseback, he often takes along a camera housed in a special padded camera bag that fits on the saddle. Other times, he’ll just rely on his smartphone to capture

a scene or image for reference.

Back in the studio, Weller peruses the photos and then selects one as his reference. If he determines that the composition is complex, he simplifies it by making a small grayscale pencil sketch, fine-tuning the design as he draws. Next, he tapes down a sheet of 90- or 140-lb. Arches cold-pressed watercolor paper, usually a half-sheet, on which to draw the scene. He may use tracing paper to transfer a more accurate likeness of the sketch. “The drawing shows me the important edges,” he notes.

Unlike many watercolorists, Weller doesn’t wet and stretch the paper prior to painting. “I don’t ever remember wetting paper except when I was in college,” he says. He doesn’t worry about the paper buckling, because he knows he can flatten it later in a dry-mount press. Dry paper, he notes, erases more easily—an important factor since, after lightly penciling in his design, he erases the lines as he paints.

Weller begins painting the areas that are most difficult, usually the faces of horses and humans. He then works on the areas where value contrast is greatest. “I sometimes do a little sketch in pencil if where I’m going is complicated,” he says, “but mostly I have it solid in my head, and that’s enough.” Simultaneously, he concerns himself with color, but doesn’t necessarily stick to those he sees in the photo. “People say that subject and color are what get a painting sold, but for me, I’m painting what I want and using colors I like, so I don’t worry about selling,” he says. “If the colors match the couch, it’s just pure luck.”

As he works, Weller tries to lay down each wash “right” the first time. If he’s uncertain, he errs on the lighter side, knowing he can layer more color later. If he wants to change color in an area, he dries part of that area and then drops the new color into the still-wet portion. Weller relies on the slope of his drafting table and a hair dryer to direct the color where it’s needed. He uses any means necessary to ensure that the color is strong and bright. “Because it’s important that the paintings look fresh,” he says, “I’m willing to wad them up and toss them out if they start to look overworked.”

Even after a lifetime of painting, Weller isn’t fixated on any particular brand of brush or paint. He has the usual assortment of brushes—tiny to large, chisel-edge to pointed. His workhorse flat edge is a 3/4-inch brush, although he sometimes uses a Japanese brush. For painting grass and horse tails, he uses fan brushes up to 1.5 inches wide.

As a watercolor purist, Weller doesn’t use white paint, preferring instead to preserve the paper’s white for lights. Unlike many purists, however, if he can’t find the exact hue he wants in a tube, he mixes color as needed. And instead of mixing paints to stand in for black, he reaches for a tube of actual black.

From Artist to Author

Weller not only lives in and paints the American West, but he explores it through the written word, too. In the spirit of embracing change, he’s now writing modern Western novels, scaling the font size large enough on the computer so he can see it clearly. Sunrise Surprise, (Don Weller Western Art, 2023), the second in his murder mystery series featuring Jake Oar, a Utah rancher and cutting horse trainer, was released last spring; it’s available on Amazon.

Weller maintains a passion for writing about art, too, as in his award-winning Don Weller Tracks, A Visual Memoir (The Weller Institute for the Cure of Design, 2022). He also recently worked with his wife and partner, Cha Cha, and watercolorist Marlin Rotach to publish The River Flows: Watercolors of the American West (The Weller Institute, 2020). The 200-page book explores two centuries of Western works by 41 watercolorists, from George Catlin (American, 1796–1872) to today’s artists.

Tricks of the Trade

A Weller painting usually features three recognizable trademarks: a sweeping backdrop, descriptive textural strokes and subtle gestural movement.

Background: In some cases, the backgrounds in Weller’s paintings serve as a simple backdrop of flat color, but in others, such as Cowboy Church, they’re part of the story and offer depth and complexity. “Sometimes, I can tell the story I want without backgrounds,” the artist says, “but usually, they set the scene and contribute to the image.” Many of the backgrounds featuring flat color have a silk-screened look. To achieve this effect, Weller uses white gouache mixed with watercolor and a little water. “If I do this, it’s usually because the painting was getting a busy surface and seemed to ask for some visually quiet places. It can also be used to cover a mistake, but that alone isn’t a good reason for it.”

Texture: “I’m drawn to a brushstroke that looks like a ‘happy accident’—a stroke that suggests a thousand acres of sagebrush, a horse’s mane or a cloud in the sky,” Weller says. “I treasure a cloud like that over a well-rendered one.” Depending on the surface, he may make the stroke first and then blend it into another area while it’s still wet. He practices these strokes—what he calls his “trick shots”—on scraps of watercolor paper first.

Movement: Weller learned to capture the gesture and movement of a figure quickly while in school. He gives as an example a model that stands contrapposto, in which the weight is put on one leg while relaxing the other leg. This shifts the hips and shoulders, introducing a graceful curve into the spine. “It’s the same whether the pose is of a standing cowboy or a horse’s stance,” Weller says. “I try to exaggerate curves and positions, but I only exaggerate a little—too much, and it gets cartoonish; no exaggeration, and I’m just duplicating the photo.”

Embracing Change

Watercolor has, until recently, been Weller’s primary medium, but because of his failing eyesight, he has been drawn to oils. His watercolor paintings require a certain amount of tight detail, which he now finds more difficult to achieve. “I’m working bigger and looser in oil,” he says, “which works better with the macular degeneration.”

What does this mean for Weller and his art going forward? “I think an artist is growing when he’s changing,” he says. “An artist can only do the same thing over and over for so long before it begins to feel stale, so I’m trying to embrace change. “If you’re in art to get rich, the odds are against it,” the artist says. “Better, I think, is to paint to please yourself and let the chips fall where they may.”

On the Trail

When it comes to the peripatetic nature of his life, consider this Weller quote from Don Weller Tracks, A Visual Memoir, which is replete with his drawings, watercolors and oils, as well as self-penned mini-essays about his life:

“I started out drawing and painting cowboys and had some complicated, but interesting, detours. … The progression of projects outside the normal realm of Western art, and what I learned from them, help give my paintings their uniqueness and personality.”

– Don Weller

These are words of wisdom for those of us who may feel that life has taken us down the wrong trail. Maybe it isn’t the wrong one, after all.

About the Author

Michael Chesley Johnson is an artist, workshop instructor and author of the book, Beautiful Landscape Painting Outdoors: Mastering Plein Air.

Meet the Artist

Don Weller (donweller.com), of Oakley, Utah, is an award-winning watercolor and oil painter. He graduated from Washington State University, earning a bachelor’s degree in fine art, and recently received an honorary doctorate degree from the San Francisco Academy of Art. He has garnered numerous art awards and recognition over the years, most recently in 2020 with the Western Heritage Award from the Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in the Literature category for his book, Don Weller Tracks, A Visual Memoir. His work has appeared in notable exhibitions and can be found at Bolt Ranch Store, in Kamas, Utah; Howell Gallery of Fine Art, in Oklahoma City, Okla.; Montgomery-Lee Fine Art, in Park City, Utah; Wilcox Gallery, in Jackson, Wyo.; and Wild Horse Gallery, in Steamboat Springs, Colo.

Enjoying this article? Sign up for our newsletter!

From Our Shop

Join the Conversation!