Six Masters and What They Teach Us About Edges, Painting, and Mood

On the Edge: Six celebrated painters manipulate line to further the mood and meaning in their masterworks.

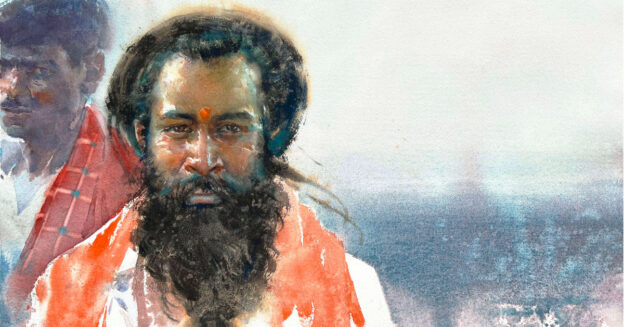

Edges are, simply put, lines, borders or boundaries that emphasize the shapes of objects in a work of art. Whether hard, soft, or lost and found, they relate to the other art elements—form, shape, space and texture, and particularly color and value—to create transitions, depth, atmosphere and emotion in a work.

This article was originally featured in Artists Magazine, July/August 2023

In this lesson, we’ll take a look at paintings by renowned artists to see how their masterful approach to edges both influences their work and drives it forward.

Jean Siméon Chardin

Jean Siméon Chardin (French, 1699–1779) painted Still Life with a White Mug as if in the dim light at the back of the pantry. Dim light calls for a soft touch. Sharp definition and edges would mar the atmosphere, because, in low light, vision lacks sharp focus. (Your mother told you to read in bright light; eyeball physiology confirms she was right.) Soft touch need not diminish clarity, however. Chardin had plenty of means to establish form and spatial relations thanks to contrasts that heighten illusions of shadow and light, and shadows that let the highlights shine.

A basic principle of paint, however, is that mixing and shading diminish brilliance in color. Generally, the more you mix, the more you dull and darken. But what if you want color in a shadow? Reflected light puts color in the border of a shadow. Especially lovely is Chardin’s leftmost pear, which is set off from the shadowy background by a splash of highlight and glowing, reflected light around the sides and bottom.

John Singer Sargent

Art historians tell us that John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925) painted the subject of Portrait of Helen Vincent, Viscountess d’Abernon in a white dress and then abruptly scraped and overpainted it as a black gown. Can we fully appreciate the British socialite’s ivory skin in anything other than black? The contours of her shoulders, cheek and swanlike neck—the sharpest edges in the painting—set off her creamy complexion against the shadowy backdrop. Sargent painted the subject’s delicate hands with fluid precision, fundamentally no less well formed than her face.

Imagine the lessened impact if the shoulder, neck and cheek line were as painterly as the forearms and fingers—or the pink wrap, for which Sargent fully unleashed his formidable painterly technique. Could he have painted the viscountess’ face with a few quick strokes? Certainly, but the sharp edges at the center of focus shine the spotlight so deservedly on her visage.

Charles Courtney Curran

Quiet, contemplative and intimate: Viewers find themselves leaning in to Lady with a Bouquet (Snowballs) by Charles Courtney Curran (American, 1861–1942). The close viewing and miniature size of the painting demand perfection in every dab and stroke and detail. Visually trace the edges. The woman’s nose is silhouetted against a crisp bright blossom, as if she sniffs its perfume; a sliver of light defines her chin, the contour subtly softening into her neck and collar. Sharp focus on her hand gradually fades to the sleeve.

Managing transition through selective focus is as critical for Curran in miniature as for Sargent in bravura scale. Selective focus is true to perception. Her profile is sharp, while her hair is seen as if in peripheral vision. Crisp highlights set off the crinkly translucent front of her hat, while the back fades quietly into the background. Her hand is clear, while her arm transitions out of focus to the sleeve, a peripheral.

Pierre Bonnard

To make a sunlit window appear bright in a painting, artists often darken the walls surrounding the window. In a real room, the viewers’ eyes can adjust to see some color in the wall silhouettes, but paint cannot easily convey color and shadow at once. Typically, dark-painted walls give up some of their color. The Open Window by Pierre Bonnard (French, 1867–1947) doesn’t feature any dark walls.

Instead, Bonnard painted the interior mostly warm against the landscape’s mainly cooler tones. Except for the silhouetted window shade, the trees are so bright and busy that the window could be a painting on an inside wall. Maybe the sharpest edge in the painting—the window shade that slices across the sky—pushes the landscape back outside. The shade is the sole dramatic shadow plane, while the black cat serves as balance and anecdote.

Bonnard also discards figure/ground clarity in favor of abstract organization, patterns and color planes. The lintel, stripes and baseboard combination is eye candy. Flattened by painterly touch and hazy edges, Madame Bonnard settles nicely into her lounge and, likewise, her lounge settles into the comfortable wall of colors. Inside and out, color is light, light as if made physical.

Georges Seurat

In his theory-driven A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884, French pointillist Georges Seurat (1859–91) defined every passage and boundary through contrasts. Every dotted dark is bounded by points of light; every warm with cool; each hue contrasted with a complement—all based on the latest theories of color and perception. Even the outer boundary is defined by a pointillist frame that varies around the perimeter to contrast with adjacent colors. Mechanical, yes, but when you walk into The Art Institute of Chicago and see the oversized painting on display, it’s luminous; even the expansive shadows glow.

Seurat’s pure colors blend in the eye—a phenomenon called optical mixing—as if with internal pixelated light. Contrasts of opposite hue and value mutually heighten and intensify one another—an effect referred to as simultaneous contrast.

Raoul Dufy

French Fauvist Raoul Dufy (1877–1953) worked for much of his career in a sweet spot of painted planes and zones, bright and clean, with over-drawings that defined his subjects. Boundaries and edges are open and ambiguous. Dufy’s dualistic style—drawing with line and painting in patches and planes—compresses his forms and space into flat abstraction.

Flatness is essential for drawing directly on the picture plane with line in abstraction. On Dufy’s flat space, condiments and apples sit adjacent with chairs and tables, though perspective of a sort supplies depth. Breezy and decorative, Still Life (Nature Morte) is a painting in the style of a drawing.

About the Artist

Ken Procter is a landscape painter and arts writer living and working in Alabama. His work can be found in public and private collections and is represented by Alan Avery Art Company, in Atlanta.

Enjoying this article? Sign up for our newsletter!

From Our Shop

Join the Conversation!