Gabriela Salazar and the Art of Fragile Optimism

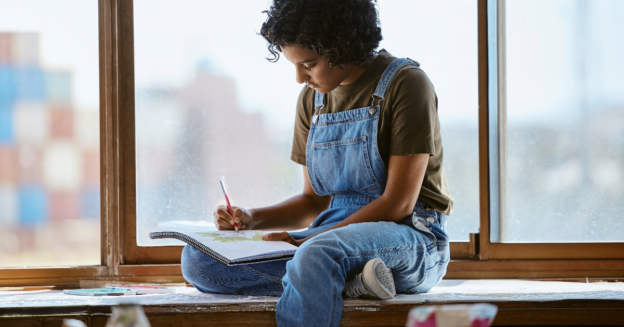

Gabriela Salazar’s installations explore our relationship with the environment—both the natural one and the built one—but she doesn’t stop there. She recently wrapped up her show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in New York City, where her piece Reclamation (and Place, Puerto Rico) explored reclaiming Puerto Rico’s agricultural independence. The work also touched on her ancestry, which includes coffee farmers who worked the land of the island. In Low Relief for High Water, another piece that has roots in her family history, she cast the windows of her childhood (and current) home in paper. She then installed the resulting sculpture in New York’s Washington Square Park and tore it apart, giving the scraps to passers-by. The piece was commissioned by the Climate Museum for the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, and it explored the vulnerability of the planet, which Salazar regards as a shared home. Her concern for the environment extends well beyond her artwork and, in the past few years, it’s also been in the classroom. At Grace Church School, she teaches the class Creativity and the Climate Crisis, and she previously taught it at Sarah Lawrence College. The course, now in its sixth year, covers not only artwork that explores the environment, but also the use of tools like charismatic facts, which present scientific facts in culturally relevant ways that grab attention and are prone to be passed along. She took a few minutes out of her busy schedule to discuss the ideas behind the course, some of the interesting—and even quite witty—projects that her students have created, and this growing movement in the art world.

John Eischeid: Could you tell me where the idea for the class came from?

Gabriela Salazar: The class was developed around the same time that I was working on my piece for the Storm King Art Center show, “Indicator: Artists on Climate Change.” Through that connection to the show, I was really beginning to think about the ways in which artists have engaged with the environment—and how that’s kind of been one of the dovetails into current artists working with climate. For example, it’s thinking through land art but then going all the way back to Thomas Cole [American, 1801–48] and Frederic Edwin Church [American, 1826–1900], using the landscape as a way to transmit ideas about American history or American Manifest Destiny. In which ways was that relationship between artists and environment telling a story about humans’ relationship or expectations for the environment?

And then the high school [Grace Church School] started a program. We have Lab Day on Wednesdays that’s a more experiential learning day. The juniors and seniors asked the faculty to propose classes that were within their interests. One of the categories was sustainability, and it just encouraged me. I thought it would be a great class, one that I’d enjoy teaching. I could touch on some environmental science, and doing that through the lens of art would be exciting. I think that first year, it was more informational and conversational—looking at art and talking about different sorts of themes, artists and responsibility to the environment.

The course has shifted, and I’ve since developed a project proposal end goal. Students now create diagrams or a model for an art project or creative project for which they are tasked to seek funding. They have to build a budget as well, for $50,000, and really think through the logistics of landing and selling the project to other people, which I think is an interesting exercise.

JE: When choosing course materials, it sounds like it was a very interdisciplinary approach, where you’re touching on some of the climate science. You’re touching on some of the language used to describe it and that idea of charismatic facts. Are you looking for your students to make a connection between all of those things—to find new connections? Have they said or done anything that was surprising?

GS: It’s come to be the overarching hope that they understand ways to approach the conversation of climate—and that they feel hopeful and possible and engaged. I think they’re young enough that they feel like the world’s already been destroyed for them, and they feel that how they can make a difference isn’t necessarily clear. My primary goal is for them to understand how art can function as a catalyst for creating community around climate and climate change action. I try to provide them with avenues to do more research and understand the science. I wish that I could get them to do even more research on the science, because I do feel like we don’t have enough time in the course to make them fully understand some of the science. That’s something that I’d like to continue to improve on. But some of the projects that they’ve come up with have been really, really surprising, even whimsical. This past year, a student developed a composting tic-tac-toe interactive game for city parks; a person spins the X- and O-marked compost bins, trying to line them up for a win while actually turning compost in the process.

JE: You see those on playgrounds for little kids, and this is like the adult version.

GS: Exactly. It could be really useful. It’s kind of funny, and it’s maybe more effective than beating somebody over the head with facts that just depress them. A few years ago, a student proposed inserting her climate poetry and other people’s poetry into publications. She would create a column, and certain syndicated newspapers could pick it up, and there could be an ongoing poetic response to climate change. Other students have focused on more architectural routes. I try to let them follow what excites them.

JE: So, what kind of backgrounds do the students come from? It sounds like it’s a very diverse group of academic disciplines.

GS: That’s right. These aren’t necessarily students who are focused on the arts.

JE: You mentioned that some of the students feel like the world has already been destroyed for them, so that kind of touches on another question that I wanted to ask you, and those are issues like climate doomism and climate anxiety. Are you addressing those directly in the class? Are you presenting art as a means to cope with those feelings?

GS: It’s definitely something that comes up throughout the class. I’m trying to help the students find ways to cut through some of that doomsday mentality. It’s a hard sell in some ways, too. I haven’t yet found a perfect reading on climate change that fits into the curriculum. It’s been even more of a challenge the last few years, as I’ve had to sort through all the information that’s now coming out about climate and art. I feel like it’s been an avalanche since I started the course. At the beginning, it was sort of like, “These are the few shows I can find on art and climate,” and now it’s much more than I can cover.

JE: It seems like it’s a constantly changing landscape. I have one more question, and then I want to get back to that. Do you feel like your students are a little bit more at ease toward the end of the course? Do you notice a change, perhaps, in their demeanors or thought processes?

GS: That’s a great question. I feel like I should ask them or take a survey and see. With some, I do. There are some students who I believe are already interested in doing something, I usually sense a kind of palpable shift that they see a way to do it. It gives them a venue to put some of their feelings into action.

JE: You touched on this kind of art that has to do with the climate that’s coming out now, and you said that there’s so much of it. I’ve been struggling to find terminology to describe it. I mean, there was Impressionism. There’s Modernism. There’s Postmodernism. But there’s this much broader movement. There’s environmental art, there’s land art, but there’s nothing that encompasses this much larger perception of addressing our relationship with nature. Sometimes it has an environmental bent, and sometimes not. Is there any terminology that you know of or have come up with to label this?

GS: I think, to your point, that there are so many different ways into this. Sometimes it’s through nature, but sometimes it’s not. In my own work, for example, I’m not necessarily referencing the environment, as we might think of it when we first hear that word, as in a built environment. I think that that’s a very valid environment—a human-built environment.

JE: There is the Anthropocene, but that has a lot of doom associated with it, and “Anthropocific” is a bit too much of a mouthful, so I’m not sure.

GS: Yes, and it’s not necessarily covering this because there are people who are also making art now, thinking through animal existence. They’re trying to decenter from the human. I think one of the critiques of anthropomorphism and Anthropocentrism is this centering on the human when there really are so many other centers that could be taken. I think that Anthropocene is a useful lens, but I don’t think it’s the only one. I wish I could help you more. “Climate crisisism?” Just “Crisisism?”

JE: Anthropocenism? I don’t know if that really rolls off the tongue quite easily enough to catch on.

GS: It’s actually good that maybe it’s not that easily definable. Maybe we’re not far enough away from it, either. I feel like it’s still in its nascent stage, although it’s picking up steam.

JE: That’s true. It needs a little bit more context before we take a broader look at it.

GS: I feel and hope that it’s actually becoming part of most artists’ conversations, even if they’re not solely focused on it, right?

JE: Yes, that’s one thing that’s come up in reading about fiction that’s coming out, and where it’s not necessarily the focus of the work, but rather the backdrop against which this larger, more human story unfolds. So, there’s this nonlinear syllabus that you have, for lack of a better word. [It’s done in Miro, a virtual desktop-like environment, that allows a user to zoom in and out on documents and images.] Is there a specific order in which you go about instructing the class, or is there certain research that you want to touch on? I’m interested in how you develop ideas.

GS: I’m looking at the board now, and there is an order. Usually, I’ll go down the left side, in almost a column format. I might start with charismatic facts, move on to Andy Goldsworthy {b. 1956; English sculptor and environmentalist who creates site-specific sculptures and land art] and then move to The World Without Us [by Alan Weisman]. We go down that line and then branch off into the things on the right. Those are kind of related to what’s happening with the charismatic facts. I have students come up with charismatic facts. They choose what to write about by researching on Project Drawdown, or another source on the sustainability research page, and we look at Goldsworthy, and they read excerpts. My goal is to find ways to creatively engage with the materials. For the charismatic facts, I have students make posters based on their fact—to consider design and communication and how to create a compelling image using information.

In the past, students have created a piece of fiction in which they contemplate the end life of this place or what would happen to it without humans. This relates to another project I do with them called “Life of an Object,” in which they have to tell the story of an object from its creation to its end through a creative medium. A student this last year detailed the story of a roll of toilet paper—on a toilet paper roll. She created a piece, in scroll format, that navigated its journey.

JE: [Laughs.]

GS: Right? That’s funny. It was very, very cute. Very often the stories are little graphic novels, things like that. I’ve had some animations that have been fun. It’s been enlightening. Too many of the students don’t realize that plastics come from fossil fuels or that the objects they’re holding in their hands are actually mined in 30 different countries. The iPhone, for example, is a complicated object that has ramifications all over the world, so getting the students to think about the things they use and how those objects reach them is eye-opening to them.

I just thought of another project. One of the Sarah Lawrence students devised it, and I really hope that she finds a way to actually do it. She created an app for children featuring real-world sustainable activities to do. The app incentivizes them from a behavioral perspective, and it also features science knowledge and a points-based learning center. It’s a little world to explore, but one that connects to organizations outside the app for real-world impact.

JE: Right! The gamification of things. There was a consultancy with businesses trying to do that—trying to get their employees to behave in more sustainable ways.

GS: Right? I think the hope is that if we reach kids early enough, what they do becomes habit. The student app developer was hoping that the players would influence their parents’ actions through the need to accomplish certain tasks, such as composting. I think it’s important that kids have this dialogue when they’re in their formative years. This is teaching them that there might be a way out—or at least a way to address things.

The same is true for older students. We can get into the nuances that the world’s not ruined; it’s just in this ever-changing state. We all need to learn how to adapt to it and work with it until we can get it to a stable place again. It’s already changing, but that doesn’t mean that we need to give up. There’s still room to work against the changes, but there are things we need to incorporate into a way of being, as well as develop a mentality that offers a little more flexibility in what the world should be like.

JE: It sounds like you’re touching more on adaptability.

GS: It’s the mentality that it’s not black or white, the thinking beyond “It’s ruined; therefore nothing I can do is right.” It’s not ruined. It has been changed, and although it’s not necessarily good change, there’s still always room to do more. I can’t say fix it, because there’s no “fixing” it, but it’s important to work against worse change.

Join the Conversation!