Snapshots in Time: Using Photos to Paint the Figure

When taken with care, photographic references can inform the mood of a portrait and help you capture a model’s emotional interior.

By Ted Nuttall

My assertion that good figure and portrait paintings can be accomplished from photographic reference is often met with raised eyebrows by advocates of painting from a live model. While I agree that there can be pitfalls to working from photographs, I like to think my paintings depict a moment of expression and emotion that can most effectively be captured with a camera. Those moments are the essence of my work.

Have Something to Say

From the beginning, my approach to painting people has been driven by ideas best expressed by two great American painters, Thomas Aquinas Daly and George Carlson. Among others, these two influenced the way I came to painting, both emotionally and technically. What they each have to say is essential to my work.

Daly, in his book Painting Nature’s Quiet Places, said: “My deep emotional involvement in my subject matter is the essential ingredient that carries my work. For years, I floundered in a quandary over what to paint until I realized the most rudimentary fact: I should paint what moves me and, if handled with some degree of facility, it should, in turn, move others.”

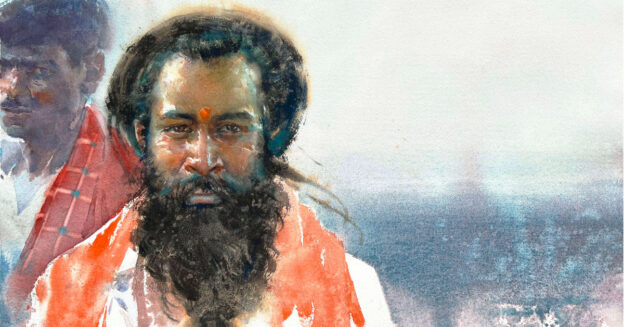

The young man in Light and Shadow (watercolor on paper, 15×22¾) was a waiter and ski bum I met when I lived in Montana. He sat for me in the studio. The strong sunlight blanketing his face and figure and the powerful cast shadows on the wall behind him created great possibilities for an interesting composition.

I also appreciate this quote from Carlson, both a sculptor and painter: “Interpretation is a necessary ingredient to art. There’s no reason to do a work if all you’re going to do is take calibrated measurements and reproduce the subject in another scale. If you don’t have anything to say about the subject you’re depicting, what purpose does it serve?”

I believe the foundation to a successful work is a combination of the connection I feel to the subject I’ve chosen to paint, what I want to say, and how I interpret that connection. Painting a portrait or figure is just as approachable as creating a still life or landscape, although I’ve actually never painted a landscape. Instead, I’ve often facetiously said that some of the best “landscapes” I’ve ever painted are people. I find that thinking of the forms, edges, and surfaces of a figure or portrait as shapes in a landscape can remove much of the intimidation one encounters when painting a nose, an eye, or an elbow. Once an artist begins to really see what those forms and surfaces look like and translates them into paint, the illusion of the figure will follow as a natural consequence.

I saw the gentleman whom I painted in Sunday In Central Park (watercolor on paper, 23¼ x14¼) sitting on a bench. I was across the street and took two shots with my telephoto lens. Back in the studio, I realized the man was looking at his grandchildren. I zoomed in on his face and saw that his feelings were evident.

Selecting a Model

I’ve been drawn to people and faces all my life; I’m a born people watcher. Yet, when I began painting, I realized that I wasn’t simply watching people; in fact, my observation of potential subjects is much more a sensory experience. Having been drawn in by a person’s outward facade, I’m sometimes able to glimpse a defining essence—an impression of his or her identity—although it’s not something I experience frequently. I can sit in a coffee shop for several hours and observe a hundred people coming and going and only experience this connection with one or two people. When it happens, that sort of understanding is both soothing and inspiring. To this day, I’m not quite certain what it is—this connection. I’ve speculated that it may be a reflection of my inner self, a glimpse of my own insecurities, cares and dreams. Or, perhaps it’s empathy and the vicarious experience of an unguarded moment that happens to all of us—a moment of struggle? Wonder? Vulnerability?

Virginia Woolf once said, “… the most mysterious and essential aspects of human beings were not their possessions or their habits, but their interior emotions and thoughts.” Inspired by that idea, I determined that these “interiors” were the things I wanted to capture in my paintings. Starting with a camera seemed a good way to begin.

The subject in Occupied (watercolor on paper, 15½ x17), Nialah, was one of the staff at a conference center where I was teaching a workshop. I asked for 15 minutes of her time to take some photos and positioned her near a window in a meeting room. She was quite a natural and quickly adapted to the situation. This photo, in particular, captured an introspective and expressive moment in both her hands and face.

Working with a Model

In recent years, I’ve been doing more photography inside of my studio, an approach that can allow for more intimate, personal interaction with my subject but one that raises its own challenges. For example, how do I keep subjects from looking too posed? How do I capture that unguarded moment of expression that drew me to the model in the first place?

Even in the controlled studio environment, I want my subjects to seem alone or lost in thought, stripped of their public persona. It might seem like I’m asking a lot, but I find that if I simply tell a model about my expectations, serendipity takes over. Often, as he or she contemplates how to accomplish my directions, the moment I’m looking for happens spontaneously.

Once I’ve placed a model under the lighting, I start taking pictures. My last bit of instruction to the model is to make subtle movements with each shutter click—a tilt of the head, a variation of direction in the gaze, a change of facial expression or the overall gesture of the body. I’ll take as many as 200 shots (thank you, digital camera) in the hopes of capturing a few magical, fresh, expressive images.

I selected this photo from multiple possibilities because of the model’s simple gesture and the soft, reflective qualities in her face. My connection to her mood brought energy to In a Room of Her Own Private Dream (watercolor on paper, 11½ x11½).

The Photograph

I tend to favor a single light source for photography. When I’m taking photos outside, early morning or early evening light is the ideal. Allowing the sunlight to strike the side of a figure produces a more dramatic effect on the face and body.

Similarly, when I’m taking photos in my studio, I prefer natural light and will place subjects near a window or doorway. Again, I choose a placement that will light the subject from one side. I’ll seldom light a model from the front, which tends to look flat. I never work from a photo taken with the flash, which also creates a flat effect and diminishes subtleties in the face while exaggerating darks and shadows.

I took the reference photo for Was She Even Listening (watercolor on paper, 13¾ x18½) in my studio, with large southfacing windows to the model’s left. I was especially intrigued with the dappled light and shadow across her face, hand and shoulder. The undulating red and yellow striped blanket provided an exciting foil to her sunlit skin and gesture.

Having a good camera is critical for getting a reference photograph that accurately represents your subject. Although there are many good cameras to choose from, I prefer to shoot with a single-lens reflex (SLR) camera. Mine is a Canon EOS Rebel. I find that, despite my limited expertise in photography, my chances of capturing a quality image are enhanced when I use it. Detail and sharpness are a necessity. What’s more, it’s of paramount importance that the light I’m seeing at the time of capture is the same light I see when looking at the photo. The SLR route ensures that the critical information in the shadows and highlights is available to me during the drawing and interpretation process.

For me, all of these processes that precede painting—connecting with the subject, finding interesting light, capturing a quality reference image—are just as essential as is paint application to the success of the final piece. With this type of careful preparation done in advance, I can begin to plan the execution of the painting, which will, hopefully, support my concept.

This article originally appeared in Watercolor Artist. Subscribe now so you don’t miss any great art instruction, inspiration, and articles like this one.

Meet the Artist

Award-winning artist Ted Nuttall graduated from the Colorado Institute of Art and is a Signature Member of the American Watercolor Society and National Watercolor Society, among others. He enjoys Master Signature status with the Transparent Watercolor Society of America and Watercolor West.

From Our Shop

Join the Conversation!