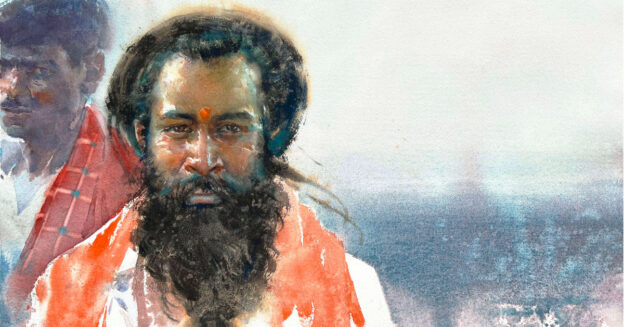

Conducting Light and Color

Steven Walker’s interest in the quality of light is like a conductor’s baton, orchestrating color, value and depth to make paintings that sing.

Working in the early morning or late evening for the most interesting lighting scenarios, Steven Walker captures an inspiring scene first with his camera and then takes the photos home to the studio. He notes that some photos make poor references for studio painting—but not in the way you’d think. “Some photos are just too good,” he says, “and should continue to exist as photos, while others need an artist to take the composition to the next, more aesthetically pleasing level.”

This article originally appeared in Artists Magazine. Subscribe now so you don’t miss any great art instruction, inspiration, and articles like this one.

In The Studio

Walker lives in Georgia with his wife, Evelyn (also an artist), and their daughter, Poppy, who—like her parents—is a creative soul. They all share a 600-square-foot studio space for their artistic pursuits, which includes a love seat and a television. “It’s kind of a living area that we also work in,” Walker says. Another unusual feature is the back wall, which he has covered with Ideapaint, turning it into a large dry-erase board for to-do lists and deadlines.

Walker keeps most of his gear on wheels: A tool chest for framing materials, a second one for a taboret, and a Best Santa Fe II easel. Since he paints all hours of the day, he needs consistent lighting, which is provided by six lamps, each loaded with four 6500ºK T8 LED lights.

Walker’s training as an illustrator naturally pushes him toward studio work. “I’m not much of a plein air guy,” he says. “For me, painting outdoors is more about taking chances and immersing myself in the environment.” When he does go out, he uses a Sienna pochade box by Jack Richeson with a matching panel holder. “I’ve found that it’s quick for me to set up, and the panel holder is sturdy for aggressive painters like myself.”

Although he uses many brands of oil paint in his work, when painting outdoors, he prefers Michael Harding paints. “There’s so much pigment in them that I don’t have to work as hard to get the maximum punch from a color.”

He rarely paints from field sketches in the studio, however, preferring to start something new from photo reference. He sorts his images, shot with a Nikon D-3100 DSLR camera, into categories such as skies, water or vehicles. When choosing a subject, he looks for something that moves him, but the choice also depends on who the painting is for. “I know that certain galleries do well with certain subjects, so I may take that into consideration,” he says. “But now that I’m a little older, I don’t try to force paintings just to get something to the gallery.”

If he ever gets stuck for ideas, he turns to a folder on his computer marked “Inspiration.” Images range from portraits and landscapes to cinematography and animation. “When I get stuck, I start scrolling through the images and often come away with an answer that I didn’t expect but needed,” he says.

Getting to Work

The more preparatory work Walker does, the faster the painting comes together. He explores design with thumbnails, created digitally in Procreate. (He sometimes posts videos of these sessions on Instagram, @stevenwalkerstudios.) He may also seek out color solutions with a few small oil studies. “Sometimes the photo is just perfect, but when it needs tweaking, I rely on color studies,” he says. He often leaves these studies unfinished because he wants to save energy and interest for the painting.

He prefers a smooth surface for painting—one that won’t be damaged by water—so most of the time he uses aluminum dibond panels. “Also, when you ship as much as I do, you want something light, sturdy, and virtually idiot-proof,” he says. (See Panel Prep for information on preparing an aluminum surface.) If he needs to paint larger than 48 inches, Walker switches to acrylic-primed linen. When shipping a painting on linen, he rolls it up and lets the framer at the destination stretch the canvas. Typical sizes for his paintings run from 11×14 to 36×48, but he sometimes opts for a 36×36-inch square.

Walker’s usual process is to paint over the course of two sessions, working from background to foreground. First, he rubs a film of Gamblin’s solvent-free fluid over the entire surface, which ensures evenness in the drying and a consistent sheen. After making an initial drawing with a brush, he takes out a 1½-inch Speedball brayer, one of his favorite tools. He blocks in the entire surface in one sitting, avoiding detail and working wet-into-wet. “I want to cover as much ground as quickly as I can,” he says. At the end, he photographs the piece and then studies it. “Sometimes, I’ll take the photo into Procreate and draw all over it. I only do this if there’s something I’m unsure of or want to change. It’s been a huge time-saver.”

The next day, he gets out his smaller brushes to add finishing touches and tighter lines. He prefers synthetic over natural-hair bristles because they don’t leave ridges on his smooth panels. To clean his brushes between colors, he keeps handy a jar of liquid coconut oil rather than odorless mineral spirits. To finish, Walker uses a painting knife to build up texture in selected areas.

The artist relies on a split-primary palette with a few extra convenience colors. “Most of the colors are bright and bold,” Walker says. “If I need grays, I can easily mix them, but I can’t make bright colors from mud.” His palette—which he uses for both studio and plein air work—includes: transparent red iron oxide or burnt sienna, alizarin crimson, cadmium red light, cadmium orange, cadmium yellow deep, cadmium yellow light, viridian, radiant blue, cobalt blue, French ultramarine and titanium white.

Workshops in Practice

Walker, like many working artists, also teaches workshops. “I don’t go in with the intent of making the students paint like me,” he says. “It’s really about helping students grow and teaching them how to problem-solve and see clearly as an artist.” To be as prepared as possible, he asks students ahead of time to provide any questions he might answer or any specific problems that he might help them with.

Walker offers this advice to students: “You need to come in with an open mind and leave whatever you think you know behind. You don’t have to take everything that the teacher gives you—just what will work for you. Some lessons we’re just not ready for, and that’s OK, but you have to show up with an open mind in any classroom setting.”

5 Quick Tips for Painting the Summer Landscape

A lush summer landscape always begs to be painted. Walker offers a few pointers for getting the most out of a verdant subject:

1

Sets goals that are reasonable with equally reasonable timing attached. No building Rome in a day!

2

Focus on atmospheric perspective.

3

Push the warms and cools of green.

4

Push depth farther than what you see.

5

If you’re painting on location, don’t forget the bug spray!

Learn More in the Artists Classroom!

If you’d like to take an oil-painting workshop with Steven Walker, check out the new Artists Network-sponsored live, online classroom experience.

Enjoying this article? Sign up for our newsletter!

From Our Shop

Join the Conversation!