Build Atmosphere in Landscapes with Color Temperature

Learn how the interplay of warm and cool colors sets the temperature and creates drama in a landscape.

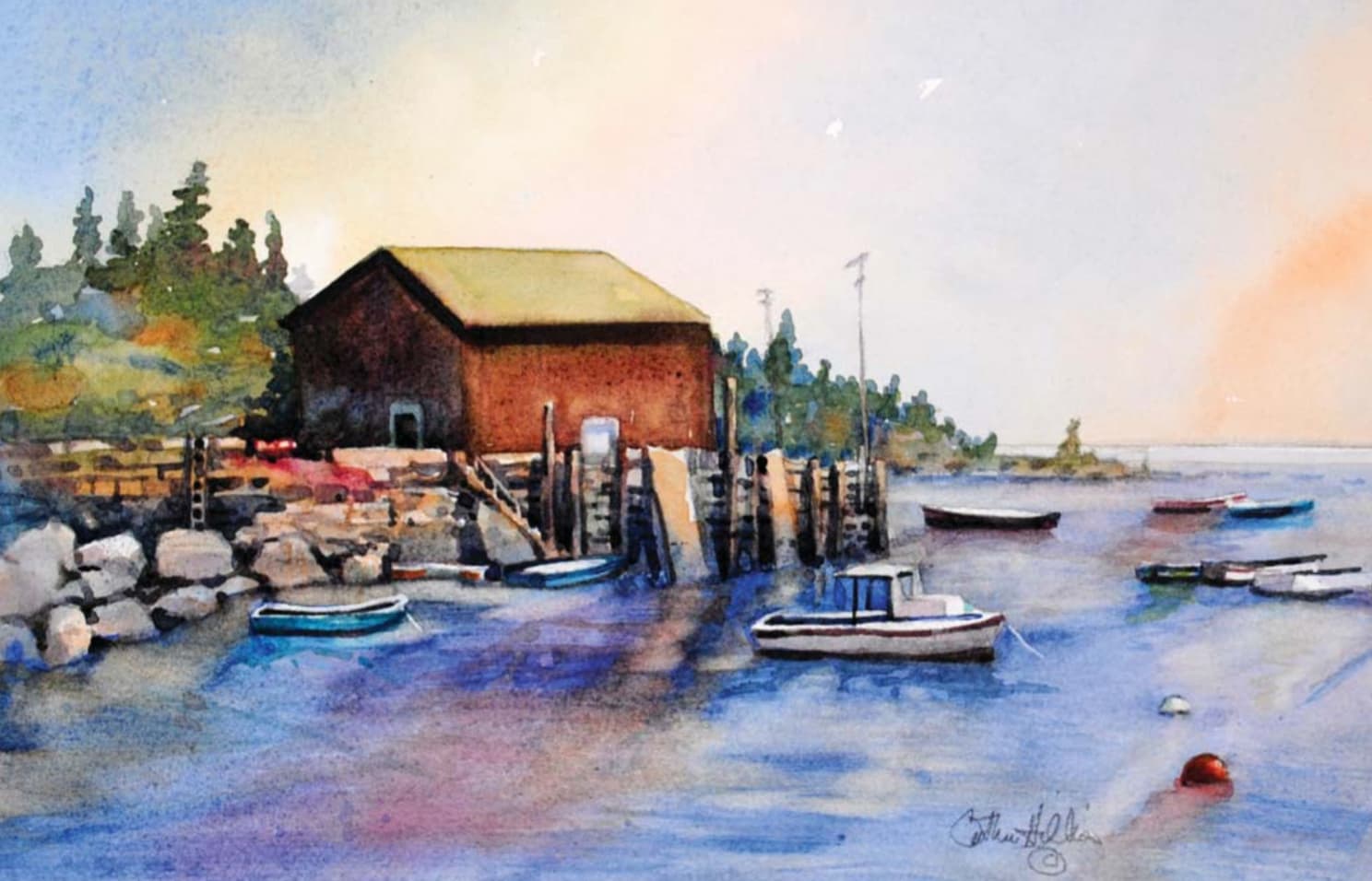

by Catherine Hillis

Painting is a complicated adventure. The more I know about the process, the more I discover I need to learn. Although I’ve been painting with watercolors for many years, it wasn’t until I began painting in plein air competitions that I understood the importance of color temperature. I believe that painting correct values is the most important factor for producing a successful painting. However, I also think that observing and painting warm and cool color temperatures will advance your skills and bring you closer to creating the desired atmosphere in your landscapes.

What Is Color Temperature?

Color temperature refers to how warm or cool a color is, depending on where it’s situated on the color wheel. Colors in the yellow, orange and red spectrum are warm, while colors in the green, blue and violet spectrum are cool.

Lighting and reflected light in the area you’re painting will influence color temperature. If, for example, a yellow traffic light is reflecting onto pavement at night, the radiated color is yellow, and the temperature is warm. If that light is red, the reflected color temperature is warm also. A green traffic light, however, will reflect a cool color temperature.

Color is relative, and its apparent temperature will depend upon what color it’s placed against. For instance, lemon yellow is labeled a cool color, because it verges toward green. However, when applied next to a cool blue, it can appear quite warm. The ambient lighting available will also affect color temperature. A lemon yellow painted en plein air in Tuscany might appear quite warm compared to the same color painted in a room with cool fluorescent lighting.

Viewing Color

I’ve found that one of the most helpful tools is a color and value isolating tool, or viewfinder. It’s surprisingly helpful and can force you to observe the color and value of an area instead of relying on what you think you see. You can make your own by cutting a 2 x 3-inch rectangle from black construction paper and punching a hole in it. Punching both a small hole and a larger hole in the card is even more helpful. Look through one of the holes at your landscape subject, or place one of the holes up against a photographic reference to isolate color, value and temperature. Or, you can purchase a viewfinder at an art supply store. Need an even quicker solution? Just squint when you’re painting to block out everything except value and temperature.

Understanding the Wheel

Within the general color spectrum are many variations. So it’s important to be familiar with the color wheel so you can identify warm and cool colors easily. It’s also important to recognize that there are cool colors, such as some blues, that paint manufacturers label warm, and warm colors, such as some yellows, that they consider cool. Because color can take on another nature when mixed with or painted next to another color, be wary of relying on paint labels alone. Always test colors for yourself.

Color in the Landscape

Observation is always the best source from which to derive color temperature. It’s important to paint what you see, not what you think you see. To achieve realistic-looking paintings, let’s take a look at four landscapes and how I’ve incorporated both warm and cool colors.

1. Foliage

Summer foliage, or greenery, is a subject for which students tend to ignore the effects of color temperature and simply pull out a tube of green. Green isn’t a difficult color to paint. You just need to consider where the foliage is warm or cool instead of painting it in a flat wash of the same color. The same is true of brown tree bark; a tree is rarely only burnt sienna.

There may be sections of warm and cool color throughout the bark and foliage. So take time to observe nature closely to see the cools and warms in the landscape. On a hot day, for example, the lower parts of tree trunks and foliage can appear cool and dark violet (Image 1, above). Meanwhile the treetops can appear warm, and bark can be a warm white or yellow. If you begin observing and then painting foliage as shapes that incorporate both warm and cool colors (Image 2, above), your greens will improve immediately.

Tip

If you’re having trouble discerning warm colors in your greens, one way to create instant warmth is to paint several underwashes of warm yellow and rose tones.

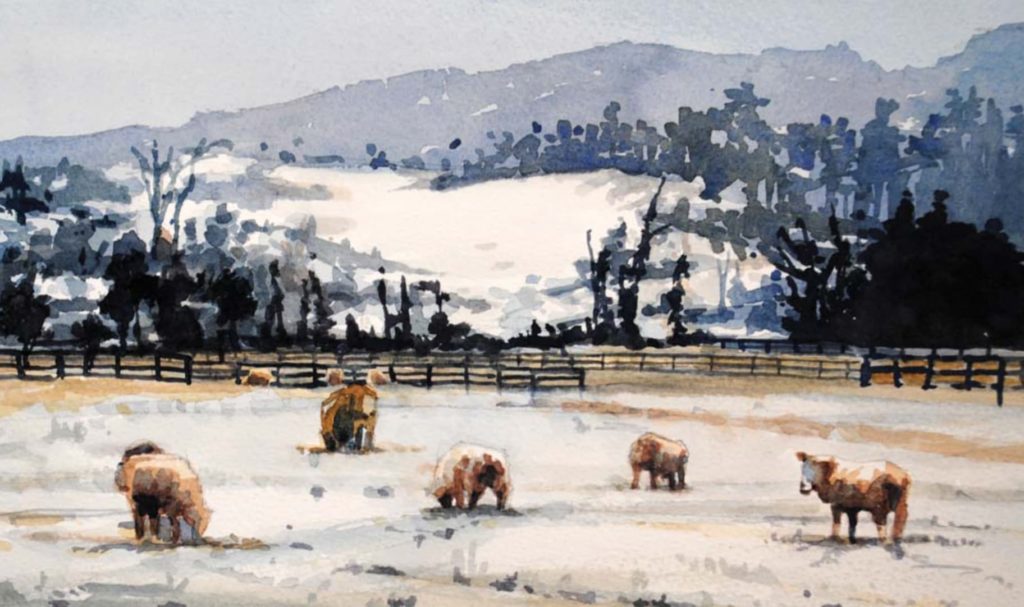

2. Snow

A good scenario for studying warm and cool colors is a snowy landscape. You might think snow is white and colorless, without temperature differences. However, a color isolating tool will help you to see warm and cool colors, as well as values, in snow.

I paint both warm and cool colors in snow, such as warm pale yellows and roses where the sun hits the snow banks, as in A Cold Meal (above). Shadows may be warm, as well, rather than blue or violet on cold days. The vertical fence posts, tree trunks and sheep absorb warmth from the sun. And that warm color bounces onto the ground and surrounding structures.

Tip

Hone your personal color temperature sensibility by using simple tools to isolate and observe color temperature.

3. Sky

When I paint the sky, I rarely use blue paint straight from the tube because the result can be a very cold color. The sun reflects warmth on everything below, even on the coldest winter day. Observe the sky on a sunny day, and you might see that it is quite warm along the horizon and would best be replicated by using an underwash of yellow and rose. These two colors create orange, and orange and blue are complements.

Tip

Using a small percentage of a warm complement with a cool color can warm that color considerably. Sometimes the upper atmosphere appears to be a warm violet blue, which might best be replicated by painting ultramarine blue, a little cobalt blue, and some quinacridone rose or permanent rose.

This chart shows blue paint colors with their complements. Blues are generally cool. In the second column, the corresponding warm complement is painted next to each blue. For the third column, 30 percent of the complement is added to each blue to create a warm dark blue. In the fourth column, a gray is painted from a 50-50 percent mix of the complements. The fifth column features blues that have about 5 percent of the complement mixed in, creating a beautiful warm sky color.

4. Water

The color and temperature of water are usually similar to what you observe in the sky. A warm blue sky, for example, will cause a body of water below to appear blue, while a gray sky will create gray water. Warm sunset colors will reflect in the water below.

There are other factors to consider when painting water. Take into account the depth and development of the background, midground and foreground. Plus consider the need to create the illusion of a body of water that lies flat on the surface of the earth and recedes into the distance. I work on creating that illusion of depth in initial painting stages, always remembering how important it is to include warm and cool color temperatures.

Step 1

In Coast O’ Maine, I painted a light mixed wash of warm and cool colors including raw sienna and cobalt blue, protecting my whites. I made a tiny “x” in pencil on areas I wanted to keep white, painting around them.

Step 2

The purpose of the second wash was to develop depth in the water and a background, midground and foreground. Depth can be created in several ways; here, I’ve utilized value to create distance. The distant horizon of the water is the lightest value, and values grow darker as I paint toward the foreground. I also can use color temperature to develop distant horizons by painting cool colors, which usually recede, in the background and warmer colors, which tend to make an area appear to advance, in the foreground.

Tip

When painting water, you can create a sense of depth from the very beginning by using value contrast and color temperature. Light to dark values create a sense of depth. Cool colors recede, and warm colors come forward.

Temperature Truths

Even though there are seasonal differences in color temperature, some things are always true:

- There’s often warm sunlight bouncing under the eaves of buildings and along other vertical shapes, and then back down onto the surface of the ground.

- Structures and objects in the landscape absorb and reflect both warm and cool light onto surrounding objects as well as on the horizontal surface.

- It’s easier to make a warm color cool when painting than it is to make a cool color warm. Under washes are a great way to build warm color temperature successfully.

Use these color temperature techniques to take your landscapes to the next level!

About the Artist

Round Hill, Va.-based artist Catherine Hillis enjoys competing in plein air events across the country and holds signature membership in several national watercolor societies. She has appeared in the Splash series three times, as well as in numerous other publications. In addition, she’s a popular workshop and classroom instructor.

This article excerpt first appeared in Watercolor Artist. Subscribe for more great watercolor instruction and inspiration!

Excellent explanation of color temperatures. Truly helpful.

Thank you.

Very well written article , instructive and informative, thankyou, I learn’t a lot.

Great article!!! Thank you!

Fabulous