Don’t You Want to Draw for Life?

Start Drawing Bodies–And You Will!

To find joy and relaxation and fun in drawing bodies, you want to learn just a bit about anatomy. Not too much! This is no medical course, but coming at anatomy from an artistic angle is the best way to go about getting great at drawing figures because you eventually will be able to draw the human body from a bunch of positions and a lot of different angles. But like almost everything, it’s better to take it a step–or a limb–at a time. Here’s a quick overview of the anatomy of the human leg and what you, as the artist, will want to look out for with a few artist exercises thrown in for good measure to get you started!

And when you are ready to jump in with more learning that isn’t going to make you feel like you are in school — Brent Eviston’s Figure Drawing Essentials: Anatomy and Form will be here waiting for you! I’m delighted to offer you this resource because it shows you how beautiful and fun and easy the process of learning anatomy can be. Enjoy!

Courtney

Beginning with the Legs

Our legs are the pillars upon which we stand. They afford us independent mobility, and our ability to walk, run, and jump is synonymous with our sense of freedom, power and personal autonomy. To use legs expressively in our work, we want to first understand the structure of the leg, both inside and out.

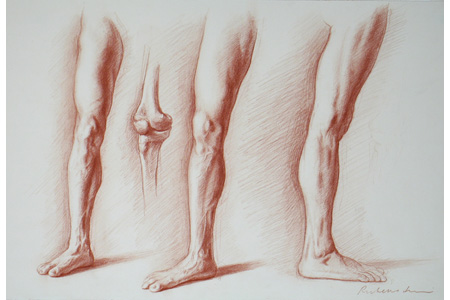

This study shows the major masses of the same leg from three different angles. Notice how the contour of the knee or calf muscle, for instance, changes as the leg is rotated. Subtle changes in rotation will greatly affect the reading of the contour.

Form and Function

The body is a complex series of levers and pulleys. If you can think about what each muscle is trying to do, you will understand its form more clearly. Perhaps the major functional principle in drawing the leg is that the movement of any part—the thigh, lower leg, or foot—is controlled by the part preceding it anatomically. Therefore, the muscles of the hip and pelvis control the thigh, the muscles of the thigh move the lower leg, and the muscles of the lower leg control the ankle and foot.

Artist Exercise

When you are studying the legs, try a few loose and broad sketches that map the movement of the leg you are drawing–even if it is at rest. It will give you a solid understanding of why the leg is positioned the way it is–and its potential for action.

Bones…

The leg is divided into two parts: the thigh and the lower leg. The thigh has only one bone, the femur, while the lower leg has two, the tibia and the fibula. Thrown in for good measure is a fourth, small, triangular bone, the patella, which protects the knee joint like a small shield.

The femur is the longest bone in the body. It is a fifth as long as the tibia and fibula. That means the distance from the hip to the knee is greater than from the knee to the ankle. Contrary to expectation, the femur does not follow the general axis of the thigh, but slants obliquely downward and inward.

Artist Exercise

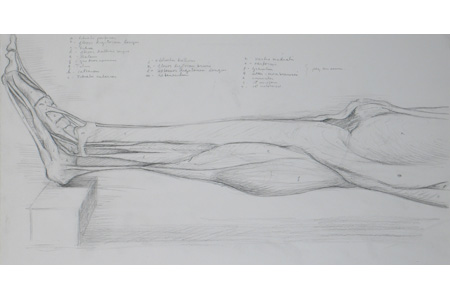

No one, least of all me, wants to spend time drawing bones. But sketching the leg’s anatomy, even in broad masses distinguished with texture or patterns to separate tendons and bones and ligaments–is a good way to go if you still want to have fun with it. As always, major shapes or masses come first!

more apparent than when examining a cadaver. The long tendons of the lower leg are particularly complicated, and this dissection required the greatest delicacy.

…and Joints

The leg has three major joints: the hip, knee, and ankle, and all offer varying degrees of movement.

Hip

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint that affords extensive movement in three general directions: flexion and extension; inward and outward rotation; and lateral movement. Moving the legs together laterally is known as adduction and apart as abduction. This great degree of flexibility allows us to execute maneuvers such as grand pliés in ballet and full splits in gymnastics.

Knee

The knee is a more limited hinge joint. The articulation between the femur and the tibia allows only for flexion and extension. The small triangular bone of the patella, the major landmark of the knee area, rides in a notch at the base of the femur. It is attached by strong tendons on top and bottom. It functions like a doorstop to prevent the leg from hyperextending forward.

Ankle

Finally, the ankle is made up of seven small bones arranged roughly in two rows. They are bound together in a shallow arch. Their articulation with the tibia and fibula allows for a good deal of flexion and extension and a lesser amount of lateral movement and rotation.

Major Masses-1

The thigh can be divided into three major muscle masses: the quadriceps in front; the adductor group high up on the inside of the thigh; and the biceps, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus in the back.

The quadriceps, named for their four distinct heads, act to extend the lower leg and to flex the thigh against the pelvis. All four fleshy bodies join in a common tendon that crosses the patella and inserts into the upper end of the tibia.

Major Masses-2

The adductor group consists of several muscles that join themselves into a united shape that is rarely subdivided. These muscles draw the leg inward toward the central axis of the body.

The back of the thigh consists of two pairs of muscles that begin together at the top, but whose tendons branch off in opposite directions below. This forms the distinctive V-shaped hollow at the back of the knee. These visually prominent tendons are commonly called the hamstrings. The major function of these muscles is to flex the lower leg.

Major Masses-3

In addition, there are two long muscles that act as landmarks to divide the three major masses. The sartorius and the tensor fasciae latae both originate on the outside of the pelvis but immediately separate as they descend. The tensor fasciae latae has a prominent egg shape when flexed but flattens out as it drops straight down to form part of the illiotibial band. The sartorius, on the other hand, moves obliquely across the thigh descending to the inside of the knee and is the longest muscle in the body.

While the thigh is extremely muscular, the lower leg is relatively boney. The crest of the tibia, the head of the fibula, and both the lateral malleolus and medial malleolus are visible right under the surface of the skin. Most of the muscles of the lower leg are relatively flat with long tendons. The gastrocnemius, however, is a large muscle on the back of the leg with two distinct heads, the lateral being higher than the medial. Along with the soleus and plantaris, they make up the calf muscle group. This acts as a powerful extensor of the foot. These muscles taper into the Achilles tendon, which attaches the leg to the heel of the foot.

The other muscles of the lower leg can be grouped as either extensors or flexors of the ankle and foot. The flexors are situated to the front and lateral side of the crest of the tibia, and the extensors on the medial and posterior side.

Tapering

Like the arm, the leg narrows as it descends, tapering supplely from the thigh to the ankle. But in addition, the thigh and the lower leg each taper individually from top to bottom. This sets up an undulating rhythm of swelling and narrowing that is incredibly beautiful.

Have a technical question?

Contact UsJoin the Conversation!