The Evolution of Figure Drawing: The Best Tips and Tricks Throughout History

Figure Drawing Methods of the Masters

There’s been a huge resurgence of interest in the practice of academic figure drawing, accompanied by much debate about the best way to draw the figure in a “classical manner.” Although it may seem impossible to add anything new in this field, below artist Robert Zeller shares an approach that can be considered an evolution of existing figure drawing methods and schools, rather than something radically new.

This approach combines three figure drawing methods adopted by significant schools of thought throughout the centuries. Enjoy!

1. Disegno

Disegno is the Italian word for drawing. But in the context of the Renaissance, its meaning is multifaceted. It encompasses not only line but also form, composition and — most importantly for us — gesture.

Gesture refers to the way rhythm and movement flow through a single figure. Gesture not only adds life to a drawing, but can help join multiple figures in a composition. This is a conceptual approach, given that no one walks around with visible rhythm lines flowing through his or her body.

The philosophy of disegno involves integrating the figure into the space around it in a believable manner.

2. The Academic Method

The method of figure drawing taught at modern ateliers is based on methodologies formulated by the École des Beaux-Arts, the principal French academy in the 19th century. The core concept of “training the artist’s eye” stems from drawing courses such as those designed by Charles Bargue (ca 1826–83) and Bernard Romain Julien (1802–71).

Schools in this tradition strive to teach artists to represent nature faithfully. They don’t all use precisely the same methods, but they generally have two points in common: an emphasis on light and shadow, and a focus on converting three-dimensional figures into flat, two-dimensional shapes. Both of these areas of emphasis emulate nature as accurately as possible.

I was trained in the Water Street Atelier system. This approach begins by blocking in using straight lines, establishing proportions and moving from the general to the specific in creating forms and subforms. Each subsequent pass brings more detailed information, all based on the dividing point between light and shadow, called the terminator.

The method culminates in a rather sophisticated conceptualization of surface form, one that is not based on perception but rather on an understanding of the relationship between surface form and light source. The result can convey a beautiful 3D illusion.

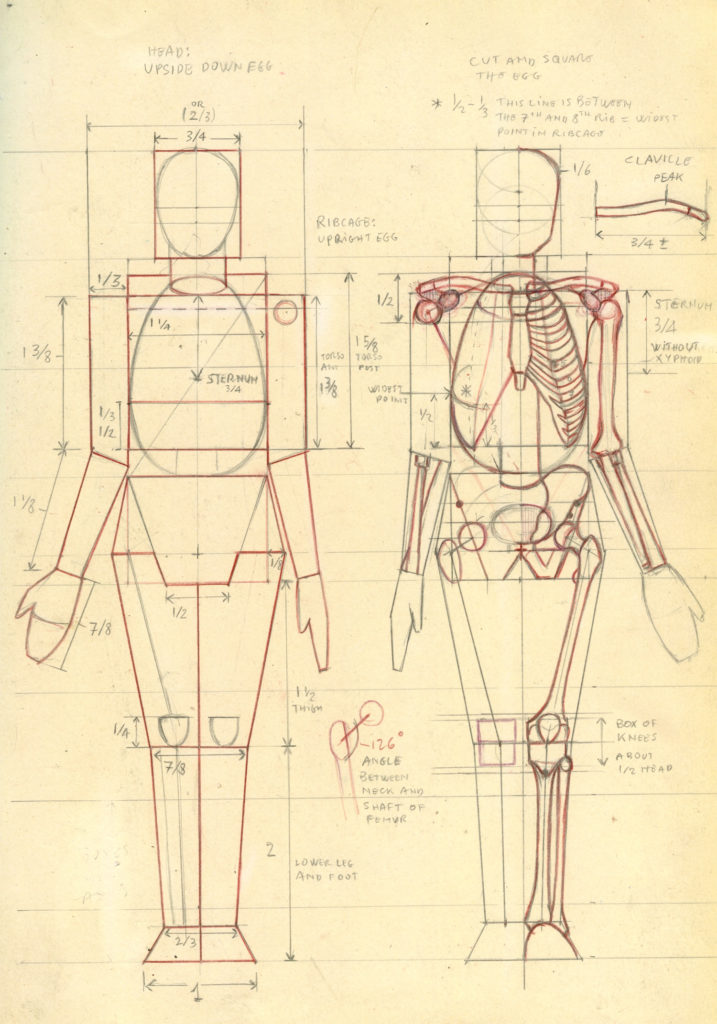

3. The Anatomical-Structural Approach

If you’re going to draw the figure well, then you have to know anatomy. For anatomy to make sense, you want to learn the interior architecture and geometry of the figure. The best approach I’ve found is the anatomical-structural approach. Though this is what I call it, it has several other names, including architectonic and stereographic.

This method has a long history, which goes back as far as Albrecht Dürer and Luca Cambiaso. I learned this approach from the sculptor Sabin Howard, who in turn learned it from the sculptor and anatomist Walter Erlebacher.

The premise is simple. Rather than memorize long lists of muscles and bones, break the figure down into geometric shapes. Rectangular blocks and cubes are usually the most helpful, but there are also cones, cylinders, ovals and spheres.

Try conceiving the body as made up of these shapes. This then provides context and function for the relevant anatomy, making it easier and more practical to remember. Artists also build a conceptual figure in their mind and compare the actual model to that ideal, conceptual model.

Draw Your Own Way

How you put these three figure drawing methods together in your own practice will be as personal for you as it is for me, tailored to your specific strengths and weaknesses. I have taught figure drawing since 2009, when I founded the Teaching Studios of Art. My motivations for creating this synthesis were practical, born of a real need to simplify the process for my students.

I hope you forge ahead and create your own variation, contributing your personal approach and vision to this ever-changing tradition.

A version of this story, written by Robert Zeller, appeared in Artists Magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.

This is a SUPER interesting subject… the description in this article is the common contemporary story that is told to students via modern ateliers. Modern ateliers have the privilege of writing their version of this history. But it is not completely accurate. It overlooks the important FACT that academic training in Europe and the America’s was completely removed from ALL formal institutions/schools/ateliers since about the 1930s… arguably earlier than that. This is proven out by the fact that one WILL NOT find A SINGLE professional academic figure drawing from the US, Italy, France, Hungary, etc. between 1940 and 1990. Not a single one. And yet, contemporary ateliers claim to understand the detailed history and technique used in Europe at and before the 19th century. A bit strange. Place a contemporary American figure drawing next to a pre 19th century figure drawing and they will look like they were produced using different techniques/philosophies. They both approximate reality, they are both figures, but there is something different…. Why? Because they are different. The contemporary version works according to ideas/methods pasted together by American contemporaries doing their best to approximate what was done in the past… but something is missing. Now, contrast with Russian Academic work — > (1) Lots and lots of academic figure drawings produced in the 20th century. LOTS! (2) Place this work next to 17th and 18th century classical works and… there is a connection. In reality drawing is drawing is drawing…. all eras from the Renaissance through the 20th century used the same baseline language only differing in regards to their dedication to a “seen object/person” versus an “idealized object/person” both adhering to the same laws of the visual illusion. …