Paint Watercolor Flowers With Light and Depth: A Demo

Achieve depth in painting watercolor flowerswith layers of transparent color and a meditative approach. Signature artist Marney Ward shows how.

By Rebecca Dvorak

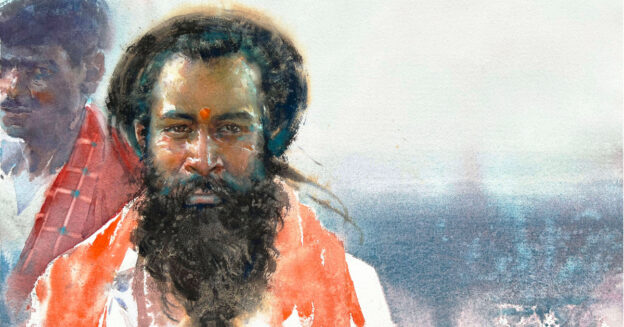

When painting watercolor flowers, Marney Ward is inspired by her garden, along with the famous Butchart Gardens near her home in Victoria, British Columbia. Ward works meticulously to capture the botanical accuracy of each flower she paints — she has an intimate understanding of various plant genuses and species. Yet she believes that the most important aspect of a painting is the feeling the subject evokes. As one viewer aptly says, Ward “captures the soul of the flower.”

The Emotional Power of Flowers

Ward imparts flowers with an emotional power through color, composition, background and, most notably, light. She says, for example, that daisies are friendly flowers, so she always paints them in numbers, as in Daisies III. A rose, however, is a singularly romantic flower; therefore, she’ll paint a solitary rose to convey its presence, as in Essence of Rose II.

When she painted white lilies, for her, the primary experience of a lily was its fragrance. “You smell them before you see them,” Ward says, so she painted dots in the background to suggest scent in Lilies in the Air, above.

Backgrounds are not an afterthought for Ward. She’ll create pulsing waves or orbs of light behind a flower or flowers to give the eye a pattern to follow. “I spend a lot of time determining what kind of background will enhance the flowers I’m working on, express the right kind of energy or direct the eye around the painting,” she says.

Capturing Light

Ward has found that light is the most effective way to convey the feeling of a flower. “I’ve become more obsessed with light as I’ve grown artistically,” she says, “and now capturing light is the most important thing. I like to say my paintings express the tangible presence of light.”

By backlighting flowers with the light shining through the petals for reference photos, Ward finds a glowing quality. “Light is the quality I aim for,” she says, “because I think that’s what people react to, that puts people in touch with something.” The darker, swirling backgrounds of her pieces work in contrast to the flowers, which become the lightest element of the composition. She initially painted botanicals with white backgrounds, “but I was in love with light. I evolved to painting darker backgrounds so that the light was predominantly focused on the flowers.”

In the painting Pink Dahlia, Ward says she played with light to give a three- dimensional quality to the flower. “I chose a strong sidelight so that the lower half of the petal is light. The central part is dark, to convey its strong, dramatic, fleshy power.” She imagined the dahlia as similar to a sea anemone, creating a background of green and blue featuring floating bubbles for a soft water quality.

A Daily Meditation Practice

Ward earned a combined honors fine arts and English degree and a Ph.D. from the University of British Columbia, where she studied the art and poetry of William Blake. Blake’s explorations on states of consciousness have been a major influence on Ward’s work. She connected with Blake’s idea that who we are affects how we perceive the world, and that reality is different in various states of consciousness.

This led Ward to try meditation in 1972, as she was finishing her dissertation on Blake. She realized that meditation allowed her to connect to her most creative self. Adding meditation to her painting practice allowed Ward to “contact the innermost levels of consciousness, where clarity and creativity reside.” She became a teacher of Transcendental Meditation and credits the practice with the blissful quality of her pieces “Meditation helps coordinate the two hemispheres of the brain so they work better together,” Ward says. It’s her practice to meditate before painting.

Ward usually paints at night, when she can focus her full attention on her practice. “It’s quiet then — no ringing phone, no responsibilities,” the artist says. “I get lost in my paintings once I start. It’s partly been the 45 years I’ve been meditating daily that have trained my mind and make it so easy to get into that painter’s bliss mode. I completely lose track of time and often end up painting until 3 or 4 a.m. It’s just a blessing to be able to paint.”

Chinese Brush Painting

Chinese brush painting, which Ward studied when she first began painting, also has influenced her work greatly. The art form has helped her master brush control. It uses a highly absorbent rice paper surface, causing the paint to spread quickly, so she also had to learn how to control the water.

The brushstroke skills and understanding of the water-to-paint ratio transfer to Ward’s watercolor work. Soft and hard edges require different approaches. For shadows, or veining, she may wait for the paper to dry for a hard edge or come in when the paper is slightly damp for softer edges.

Understanding how to work with brushes and water enables Ward to determine “the value, the quality of the edges and the intensity of the color.” Traditional Chinese brush painting compositions also feature strong diagonals, which Ward has incorporated into her work.

Color Intensity

Ultimately, however, it was the light and color of watercolor that transfixed Ward as an artist. “I love the transparency of watercolor, and the way you can get unique textures and special effects with granulating pigments, salt,” she says. Watercolor is perfect for florals because the colors are clear and delicate, but also can be intense,” Ward continues. “I build up transparent layers of color for a sense of depth.” She keeps the values light for luminosity, allowing the white of the paper to shine through.

The Process of Painting Floral Watercolors

Ward begins with her own reference photo, cropping to fit the proportions of Winsor & Newton 140-lb. cold-pressed paper. She grids both photo and paper to help her accurately freehand-draw directly onto the paper. Next, she begins painting the background, wetting carefully around the main flower or flowers. “I don’t use masking fluid unless there are tiny stamens projecting into the background. Those would be almost impossible to paint around and still have a fluid wash behind them,” she says.

She works wet-into-wet for most of the background, sometimes using salt to create a halo effect or orbs to move the viewer’s eye. For a composition with multiple flowers, Ward focuses on the distant ones first and finishes with the most prominent flower. “I usually paint that flower with a hard edge and in more detail,” she says. “I work my way around the outer petals first and then gradually into the center of the flower.” She protects the whites and lights until the end, to preserve the glow. Ward uses mostly Winsor & Newton paints, sometimes mixing in a Daniel Smith or M. Graham.

In the end, it’s the emotional impact and not the botanical accuracy of the flower that makes Ward’s paintings powerful. “All other decisions along the way relate back to that feeling I’m trying to capture.”

DEMO: Painting the Tree Peony

Marney Ward starts with a feeling on which all creative decisions hinge. Here, she describes her process for painting the delicacy, tenderness, and fragility of a tree peony.

The Artist’s Toolkit

- PAINTS: Winsor & Newton: permanent rose, alizarin crimson, quinacridone gold, aureolin (yellow), sap green, cobalt blue, French ultramarine blue, Winsor violet, burnt sienna, new gamboge (yellow) (or try Indian yellow or M. Graham’s gamboge)

- SURFACE: Winsor & Newton 140-lb. cold-pressed

- BRUSHES: variety of round brushes, mostly synthetic or synthetic blends; scrubber made by cutting down the bristles on a small oil brush

Reference Photo

I take my own reference photos. This one is of a tree peony in my backyard. This blossom caught my eye because it was paler, more transparent and more delicate than the others. I cropped the photo for composition and to fit the proportions of the paper.

Step 1

I gridded both the photo and the paper into 16 rectangles by quartering each side. Then I drew freehand using an F or H mechanical pencil; the slightly harder lead is less prone to smudging. I was careful not to press too hard to avoid creating depressions in the paper. I sometimes make little notations to clarify areas that might be confusing.

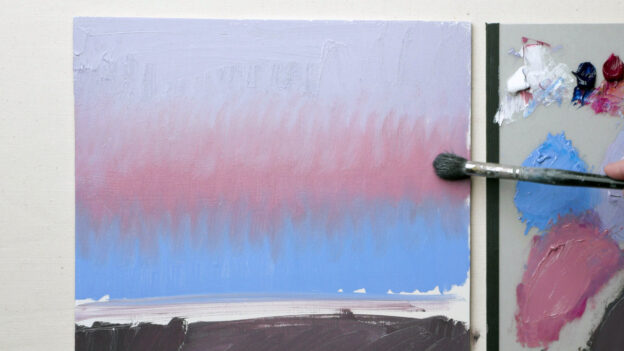

Step 2

I always paint the background first, and here I started with the top, keeping it wet for mostly soft edges. I wanted a variety of mostly light and muted greens to give the impression of dappled light. My warm colors were sap green, aureolin (yellow), new gamboge (yellow), quinacridone gold and burnt sienna, with French ultramarine blue and Winsor violet for the darks or more muted greens. Even the leaves’ red veins (top right) were done wet-into-wet to produce a soft, broken effect. I painted one leaf at a time, but I wet carefully around the flower petals, as I wanted those edges to be crisp.

Step 3

I continued with the lower background, using darker greens to give weight to the overall composition; these leaves were also more in the shade. I painted the red stems wet-into-wet where I wanted them soft, but hard-edged (dry) for the main stems. I then painted the peony’s petals, using a lot of water to keep the colors smoothly blended and light in value. For the darker petal in the upper left, I used alizarin crimson and Winsor violet for the dark streak, and added the transparent shadow on the bottom when the underlying color was almost completely dry. To create the shadow color, I added a bit of sap green and French ultramarine blue to the underlying pinkish color.

Step 4

I completed the outer layer, skipping petals to ensure a dry area on either side of the petal. My favorite petal is the large one on the right; it was so silvery, with a variety of soft pinks in the middle. I kept the white bits near the bottom paper white for maximum glow. It’s mostly quite wet for soft, gentle blending, but I wanted a few drier lines near the bottom to accentuate the light there. The darker petal below it was primarily permanent rose and new gamboge, adding that dark streak — while it was still wet — with permanent rose, burnt sienna, Winsor violet and French ultramarine blue for granulation. When the outer layer was complete, I started on the inner layer of petals.

Step 5

As I completed the inner petals one at a time, I paid close attention to the colors and values on the reference photo, electing not to go as dark as parts of the photo. I added new gamboge near the bottom of the upper petals for that glow coming through, and alizarin crimson at the base of a couple of petals. Around the lighter parts of the center, I painted carefully, since I wasn’t using masking fluid. As I added grayish streaks and the shadow of an underlying stem near the base, I keptthe transparency of the petal at 7 o’clock. Overall, I wanted to create a shimmering effect with subtle changes in value and color.

Step 6: Final Painting

To avoid disturbing the center, I first checked the entire painting for a final balance of values, darkening a few areas and lightening up others. Then, I started the center by painting the yellow stamens with new gamboge, and then the darker brownish shadows using burnt sienna and a bit of blue or purple. To create the reds, I added new gamboge and quinacridone gold to the permanent rose on the warmer left side, and added Winsor violet and French ultramarine to the permanent rose on the darker right side, keeping it mostly wet and suggested. I extended the reds and yellows into the base of the petals on the left side. The warmth and darkness of the center really brought out the delicate, diaphanous quality of the petals in Tenderness (watercolor on paper, 14×21).

About the Artist

Canadian artist Marney Ward lives in Victoria, British Columbia. She has signature status in the Society of Canadian Artists and the Federation of Canadian Artists. She has won major awards in provincial and national exhibitions, and has been published in many books and publications. After teaching for 20 years, she recently developed her own international online course on floral watercolors. Visit marneyward.com to learn more.

Writer and editor Rebecca Dvorak, of New York City, studied art history in college. She has interned with Galeria Cartel, in Granada, Spain; D.C. Moore Gallery, in New York City; and The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A version of this article first appeared in Watercolor Artist magazine.

Join the Conversation!