Low-Residency MFAs

Offered by a growing number of art colleges and universities, low-residency MFA programs appeal to nontraditional students—particularly those already with jobs, families and roots in a community.

As seen in Artists Magazine, July/August 2023. Subscribe now so you don’t miss any great art instruction, inspiration, and articles like this one.

Donna Woodley has a B.A. in accounting and worked in that field for 20 years until deciding that she could be something more than a responsible taxpayer. The Nashville resident wanted to pursue her interest in painting, perhaps even teach art at the college level someday. “With a career of counting dollars and cents behind me, I knew that I had to continue working to earn a living while completing a Master’s program,” says Woodley.

So after earning a second B.A. in studio art from Tennessee State University, at age 41, she enrolled in a low-residency (low-res) MFA in Visual Arts program through Boston-based Lesley University, which she completed two years later.

A Growing Trend

An increasing number of art colleges and universities have been offering low-res Master’s programs in a variety of fields. Lesley University, for instance, has low-res programs in creative writing and clinical mental health counseling, as well as in visual arts. Fifteen of the 35 member colleges of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design currently offer low-res MFA programs, and low-res programs for Master’s degrees currently can be found in universities in every state. They serve a population that often is older than most students in traditional full-time, on-campus MFA programs. Woodley noted that in her cohort the age demographic was anywhere from 22 to 62, and people were at a stage in their lives in which they were unable to “uproot themselves to attend grad school—many have jobs and families, for instance,” says the artist.

Joe Bun Keo, 36, an exhibition preparator at the Wadsworth Atheneum, in Hartford, Conn., is the sole income provider for his family of four. He also has caregiving responsibilities at home, since his wife has several chronic ailments, and both of his children are on the autism spectrum. Pursuing his bliss wasn’t an option, but the low-res MFA program at Pacific Northwest College of Art (PNCA), in Portland, Ore., made it possible for him to continue his work at the museum and maintain his responsibilities as a husband and father while allowing him to obtain the credentials necessary for teaching at the college level. “Those three letters—MFA—carry a market value and enable me to apply for the types of jobs I really want,” says Keo.

Programs vary from one institution to another. Lesley University offers a two-year program, with 10-day residencies on campus twice a year, in January and in June. PNCA’s program takes three years, with three, eight-week summer residencies. The residencies at Maryland Institute College of Art’s (MICA) program require students to spend six weeks on campus in the summer and over the Martin Luther King, Jr. weekend.

The on-site residencies there and elsewhere are busy periods, with students taking courses in critical theory, exhibiting and getting faculty critiques of their work— all while enjoying face time with instructors and other students. For the remainder of the year, students complete assignments and work on their art in their own studios. They’re looked in on by mentors in their home states who’ve been approved by the colleges.

For instance, at Maine College of Art and Design, students are matched with mentors who live nearby so they can meet with them at their studios once every two weeks. When they’re accepted into the program, students put forward names of local artists who could serve as mentors; the college also often has contacts in the community to propose for the role. Through a process of discussion, a personalized program is created for each student.

Professionals as Students

“The low-residency structure is ideal for anyone who can’t just drop everything—family, job, life—to move to a different city and pursue a regular MFA program,” says Fabienne Lasserre, director of MICA’s low-res program. “It’s also ideal for art practitioners who want to commit to a long-term engagement and a deep reconsideration of their art practices.”

At times, as many as half of the students in MICA’s program are schoolteachers, and most of them are in their 30s. In fact, the MFA option there, and at most other educational institutions with low-res Masters curricula, was initially designed for public school teachers who had an interest—and their summers off.

Over the years, the population of students interested in low-res programs has expanded to encompass would-be artists with jobs in other fields—people who look to art as a second career, women with children, artists who live in rural areas or at some distance from a school offering an MFA, and artists who already teach at the college level but need a Masters degree to advance to full-time employment.

“I knew that I had to continue working to earn a living while completing a Masters program.”

—Donna Woodley

One such artist is JoAnne Schiavone, a sculptor in Dallastown, Penn., and an instructor at York College, who earned her low-res MFA from Philadelphia’s University of the Arts, in 2008, at age 54. “I got a pay raise,” she says, as the result of obtaining her MFA. “They pay you more when you have a graduate degree.” It also made her eligible for a full-time job there, though thoughts of that are on hold for the moment while she pursues exhibition opportunities. Married, exhibiting and selling her work, teaching at a college and in workshops, the low-res option afforded Schiavone the freedom to “make shifts in the work I was doing in my studio without having to totally leave my life.”

Some of those shifts might have occurred anyway, but the artist cred-its her low-res MFA with helping to speed up the process. “I heard a lot of voices, a lot of different perspectives, and I was pushed harder by people in the program than I would have pushed myself,” she says.

Similarly, printmaker Pepe Coronado earned an MFA through MICA’s low-res program at the age of 40, even though he already had a teaching position at the Corcoran School of Arts, in Washington, D.C. “I knew that an MFA is required to teach full-time at most colleges,” he says. “I knew I needed to learn more in order to do better work.” Keeping his job at the Corcoran enabled him to pay for his tuition, and he had no reason to believe that the university would have held his job for two years had he opted for a residential MFA program.

A Wise Investment

It doesn’t cost any less to be a low-res MFA student relative to one who is earning the degree full-time on campus, although there may be fewer fees to pay, such as those covering student life, technology and the use of studio spaces. The administrators of low-res programs strive to match the rigor of on-campus programs.

“Our program is built to mirror the intensity of our full-residency Visual Studies MFA. The contact hours are concentrated into summer and winter ‘residency’ sessions that I liken to adult summer art camp: fully immersive, with coursework and studio work plus a different visiting artist every week. We have a written thesis exhibition and public defense. It’s very rigorous.”

Ryan Pierce, the chairman of PNCA’s low-res MFA

In some ways, more may be asked of low-res MFA students than of their on-campus counterparts, according to Amy Justman Giese, director of the Massachusetts College of Art and Design’s (MCAD) low-res program. “Because many

low-residency MFAs have a non-traditional structure, such as monthly mentor meetings rather than weekly classes, students need to be self-motivated and independent in their work,” she says. “Also, because students aren’t on campus for the majority of the year, they need to have the means of creating studio work in their home environment, whether that’s a makeshift kitchen studio or a room dedicated solely to art-making.”

There appears to be no stigma to having received a degree from a low-res program as opposed to going a more traditional route. Lasserre notes that MICA’s low-res MFA graduates “are very active in a multitude of art contexts across the country. They teach art, have shows, organize shows and have the same types of careers as those who earned degrees from the residential programs.”

Craig Stockwell, a painter in Keene, N.H., who received a B.A. from the Rhode Island School of Design and an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts (VCFA) through its low-res program, notes that he was hired almost immediately as

a college art instructor at Keene State College after completing VCFA’s program. Subsequently, the artist has taught in low-res MFA programs at Lesley University, the New Hampshire Institute of Art and MCAD.

Before enrolling in VCFA’s program, Stockwell noted that he felt isolated artistically but wasn’t in the position to pick up his life and move away to go back to college for two years. “I had kids and a job—I needed flexibility in my schedule,” he says. “These types of options are becoming more and more interesting to people.”

About the Author

Daniel Grant is an arts writer and the author of six books on building a successful art career, including The Business of Being a Writer.

Enjoying this article? Sign up for our newsletter!

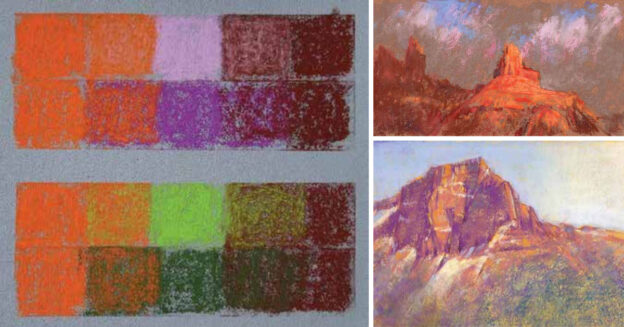

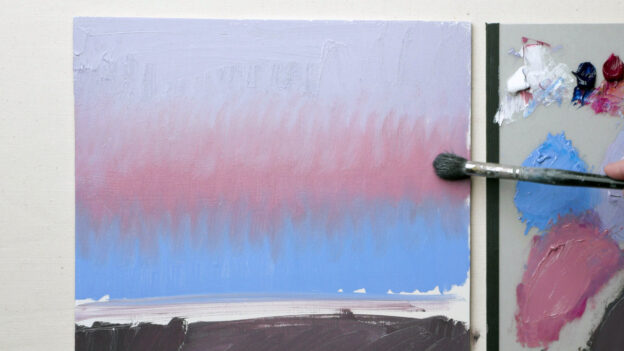

From Our Shop

Join the Conversation!