The Big Picture: Rick Shaefer’s Large-Scale Drawings

With an infusion of influences both past and present, the supersized drawings of Rick Shaefer—the Juror of Awards for the 16th Strokes of Genius 16 Drawing Competition —draw their power from the active, loose, energetic line he makes primarily with compressed charcoal in pencil form.

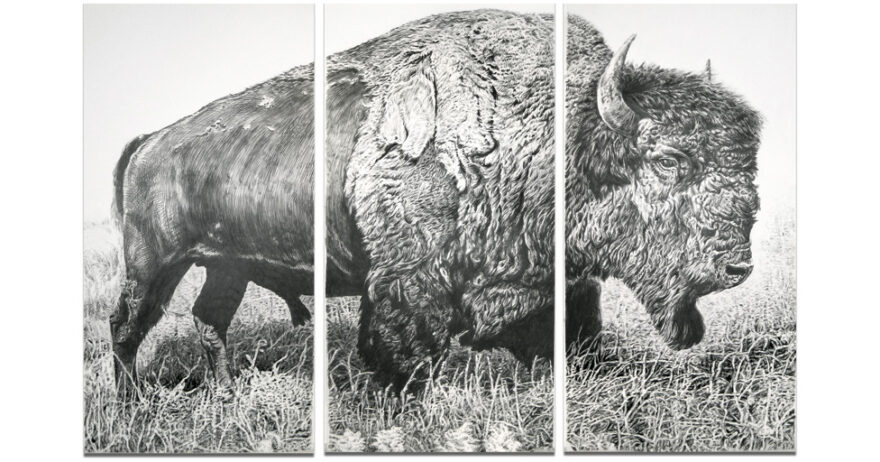

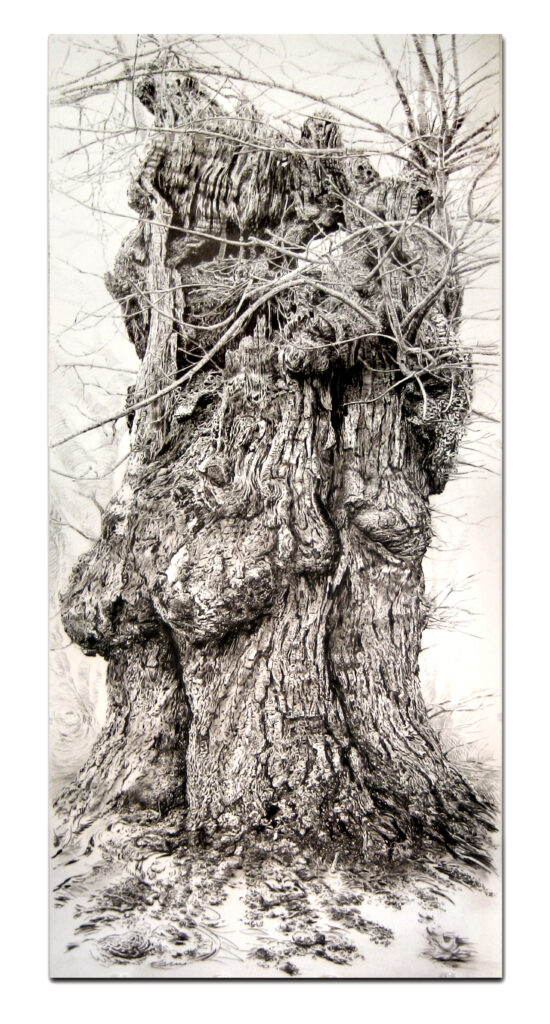

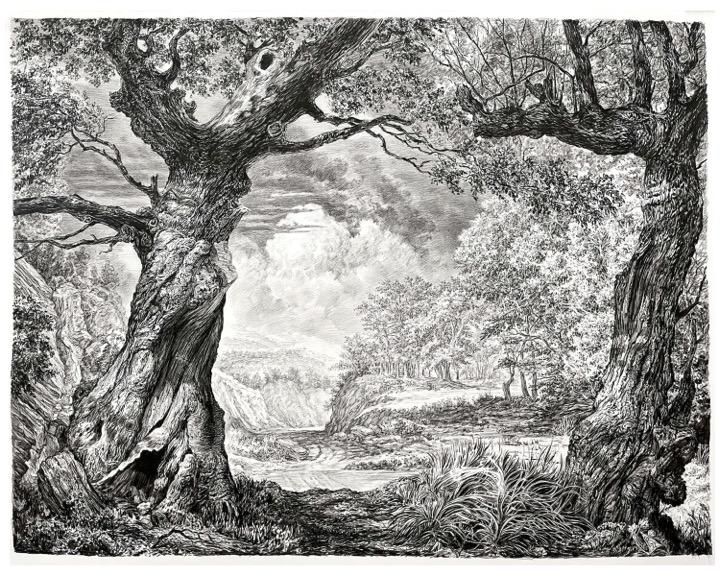

An air of history hangs around the drawings of Rick Shaefer, as though they might have been made at some indeterminate point in centuries past. Bucolic landscapes with fulsome trees and distant vistas might be part of the same idyllic and somewhat fantasized world beloved of Flemish masters like Pieter Breughel the Elder (ca 1525–63) or Joos de Momper the Younger (1564–1635). On the other hand, some of the subject matter feels quite contemporary, with images of endangered species and compositions with pointed political references. Furthermore, the general snap and energy of the work seems very much of this moment.

Most of all, the enormous, even spectacular, scale of the drawings—some as large as 19 feet across—places them squarely in the modern age. These drawings, then, are works that borrow heavily from historical techniques and imagery, which then are refit and modified for contemporary use. Their tonality, with rich darks and pristine lights, initially suggests that engravings might be the main influence, but closer examination reveals none of the mechanical hatching that engravers employ. Rather, in Shaefer’s drawings, the tone is built with active, loose and energetic line. It’s a line that not only sets tonal values but also describes form and creates powerful graphic outlines.

“I love engraving’s disciplined line work, but I only mimic it occasionally for fun,” says the artist. “It’s more the scribbles and flourishes of etching that have influenced my drawing style. I like to be more gestural and spontaneous, laying down marks quickly and keeping the pace moving.” Further explaining how his work differs from engravings, he says, “Engraving, though fabulous, is way too principled and disciplined for my personal style. I love that people can get up close to my work and just see a mass of scribbles and then back off and see the image coalesce into an almost photographic clarity.”

Lines of Conviction

As Shaefer first began working on his monumental drawings, he mainly found his subject matter near his home in Connecticut. “My first drawing on a large scale was of an oak that had fallen in a neighbor’s field after a storm,” he recalls. While the image of a fallen tree was a perfect technical vehicle for the kind of drawing he wanted to do, that subject also fell in with the artist’s desire to say something about his feelings for the natural world and our stewardship of it. He went on to make a number of large drawings featuring members of endangered species, such as the American bison.

“I try to make my work embody a sense of urgency while, at the same time, appear fairly still and possibly even somewhat bucolic on the surface,” Shaefer says. “I feel we’re heading down a rathole, an almost inevitable spiral of misdeeds and mismanagement of our own lot and that of the planet we call home. My animal pieces are cries for kinder and more enlightened stewardship—a plea for us to share the planet, not just subjugate and exploit it.”

Big Picture Challenges

How exactly are these drawings constructed? “Sometimes I’ll make a loose study just to get the overall composition,” says Shaefer. “More often, I like to have bits of reference to work from as a framework. Sometimes I’ll do a complete photo montage of assorted scraps pulled together in order to have a more concrete visual before me when I start the actual drawing.” The artist finds good references, photographic or otherwise, helpful—especially for certain passages. “That way, I feel ‘covered’—safe to dive in,” he says. “Then, once I’m fully underway, I can riff on the references or even ignore them.”

Scaling up from his sketches and references presents a bit of a challenge. The artist has tried using grids but now avoids them. “The problem with a grid is getting rid of it during the process,” he says. In fact, with or without a grid, he finds that creating a fairly detailed preliminary sketch or outline on his drawing surface can be problematic. “I find those too constrictive, too limiting, and they seem to get in the way of the spontaneity of the final mark-making,” says Shaefer. “I prefer very loose, very ephemeral and light marks on the surface, just enough to orient me, so I know where larger elements should sit.”

Placing these guiding marks might involve simply measuring with a ruler to establish where one or two salient points in the composition fall. These fixed positions mean that the drawing won’t get too far out of hand once the process begins. “Then I can refer to the preparatory sketch or reference in a fresh way that allows vagaries of the moment to happen,” says the artist. “The magic moments and passages always seem to come from the gut or spontaneous flourishes rather than overly planned and charted procedures.”

Materials and Methods

Shaefer usually draws with paper-wrapped compressed charcoal. Because that medium smudges easily, he takes great care with the position of his hand while working. Being right-handed, he starts in the top left-hand corner and gradually works his way across the piece, building each section considerably as he travels down toward the bottom right-hand corner. When using media other than charcoal, he’ll wander about on the surface more freely. Occasionally he’ll go back into a piece using black ink, working into the darks to create greater richness and contrast.

Drawing on such a large scale also brings the challenge of presentation. Much of Shaefer’s work is made using synthetic papers, which he then fixes heavily so that the works can be displayed unframed. He pierces some of the very large pieces with grommets, so they can be hung in the manner of a tapestry. Recently he has been doing more work on traditional paper that must be framed behind glass.

The artist’s supplies include:

✓

Substrates: vellum and synthetic vellum, drafting film, Tyvec and a wide assortment of papers

✓

Charcoal: “Mostly I use General’s compressed charcoal in pencil form,” says Shaefer. “Occasionally I use stick or vine charcoal, and very occasionally I use charcoal powder as toner for the background. I also use liquid charcoal.”

✓

Darkening media: Because the fixing process can tone down the charcoal in the deep shadows, Shaefer likes to give those areas a boost, using one or more of the following media: Stabilo Aquarellable black pencil (which he uses for general drawing as well), Conté watercolor pencil, ink (brushed on or applied with a brush marker), oil or acrylic paint (brushed into deeper shadow areas)

✓

Graphite: The artist uses graphite occasionally for light passages.

The Best of Drawing 2024!

If you aren’t using a stepladder to complete your drawings, don’t worry. Our annual Strokes of Genius drawing competition celebrates inspiring drawings large or small! If you work in drawing media of any kind (graphite, charcoal, pastel, ink, scratchboard, etc.), don’t miss your opportunity to earn recognition, along with prizes and publication. The final deadline for Strokes of Genius 16 is June 18, 2024.

About the Author

John A. Parks is a painter, a writer and a member of the faculty of the School of Visual Arts, in New York City.

About the Artist

Rick Shaefer studied at Duke University, in Durham, N.C., and the Art Center: College of Design, in Pasadena, Calif. He interrupted those studies to immerse himself in the art worlds of London and New York City, and received a B.A. from the University of Maryland while living in Europe. Shaefer built a 12-year fashion-photography career in New York before going back to painting and drawing. He has twice received a Pollack-Krasner Foundation Grant and has exhibited his work widely in the United States. His work is part of many notable collections, as well as many private collections. Shaefer’s work is represented by Sears Peyton Gallery, in New York City. Learn more about Shaefer at rickshaefer.com, and follow him on instagram @rickshaefer.

From Our Shop

Join the Conversation!